In preperation for "Tsujigahana - Atsushi Ogura's 77th Birthday Exhibition" from March 8th to 10th, 2024, we ventured into the heart of Kyoto's Kamanzadori to visit Atsushi Oguras workshop where craftsmanship and beauty intersect.

A maestro in the art of Tsujigahana dyeing, Atushi Ogura opened his doors to reveal the meticulous techniques and passion that go into creating each one of his unique kimono.

Graciously, he agreed to let us share these insights with you. This showcase is a rare glimpse into the dedication behind Japanese textile art, promising to be an enlightening experience for all. Don't miss the opportunity to explore this artistic journey online.

From a family known for Yuzen, to a family renowned for Tsujigahana.

Atsushi Ogura is the fifth generation of the Ogura Family. One of the three prestigious households among Kyoto's major dyeing workshops: Ogura Manjiro, Tabata Kihachi, and Ueno Tameji.

The Ogura family, with a history of over 140 years in the industry, were originally renowned for their Yuzen dyeing. It is during his fathers era, Kensuke Ogura, that the Ogura family came to be known as masters of Tsujigahana dyeing.

Fourth Generation; Kensuke Ogura(1897~1982)

As a Yuzen craftsman with exceptional artistic skills, Kensuke Ogura was chosen to lead the Ogura family workshop. He married into the family, to Ogura Manjiros daugther, making him the adoptive son, and fourth generation of the Ogura family.

Not content with focusing solely on Yuzen, he sought to create his own unique style by learning and mastering Shibori dyeing at his mother-in-law's family workshop, the Okao Family. He introduced a new style that blended Yuzen and Shibori, earning a reputation as Ogura Shibori. This marked a change in the family destiny.

Fifth Generation; Atushi Ogura (1946~)

Born as the eldest son of Kensuke Ogura, he was immersed in a world of kimonos, brushes, and dyes from a young age, creating his first work at just 14. In his late 30s, he became involved in the restoration and repair of important cultural properties, including kosode and haori belonging to Tokugawa Ieyasu, thereby mastering ancient craftsmanship through preservation. He is arguably the only dyeing artist in Japan with a broad range of knowledge and skills that span from Muromachi period Shibori dyeing techniques to contemporary techniques.

Within the studio lies a tea room, where aestheics and a welcoming spirit thrive.

The Ogura family has called Kamanzadori, home for just over 100 years. This street in Kyoto famously houses kimono craftspeople; In the mid 20th century 60% of its residents were in the business. Back then, the area was so dense with dye studios and kimono workshops that it was said you can walk down the street and see a kimono being made from start to finish.

These days, only two workshops remain, one of them being the workshop of Atushi Ogura. The massive decrease in craftspeople in the area has proved difficult in sustaining the trade.

In 1921, a Japanese-style house was designed and built by Ogura Manjiro, Ogura Atsushi's father in law. His wife was an avid fan of tea ceremony, so the home was constructed to be the perfect teahouse. In the back, lies the workshop. It is unual for a workshop like this to have a tearoom, adding to the charm of the home studio.

Upon entering the tea room, your eye is drawn to a small folding screen in the corner. It is dyed in the style of Tsujigahana by Ogura himself. In the tokonoma, or alcove, a work of calligraphy by Sokuchusai Soushou, is displayed proudly. Seasonal flowers are neatly arranged in a bronze vase, which is apparently nearly 300 years old. Like all visitors, we were greeted with a bowl of frothy macha, along with yukimochi, which was made specially to be served upon out arrival by the closeby Surugaya in Nijo.

Among the various teabowls included an Oribe piece and a black Ohi tea bowl , were admired for their attention to detail and consideration, reflecting the aesthetic consciousness that accompanies this exhibition.

When Ogura Atsushi was around 12 or 13 years old, the second floor of the workshop was a hub of learning and discussion. Along with human national treasures in Yuzen, Kako Moriguchi, and in Ro, Takeshi Kitamura, as well as members of the craft association, gathered almost weekly for study groups. Ogura did not directly receive design guidance from his father but was instead mentored by Moriguchi. In his late 30s, his mentorship shifted to Moriguchi's son, Kunihiko Morguchi who was 6 years Oguras senior. Ogura's workshop is located about a five-minute walk from Morikuchi's studio.

Tsujigahana, which emerged in the Muromachi period and quickly disappeared in the Edo period, still remains largely shrouded in mystery.

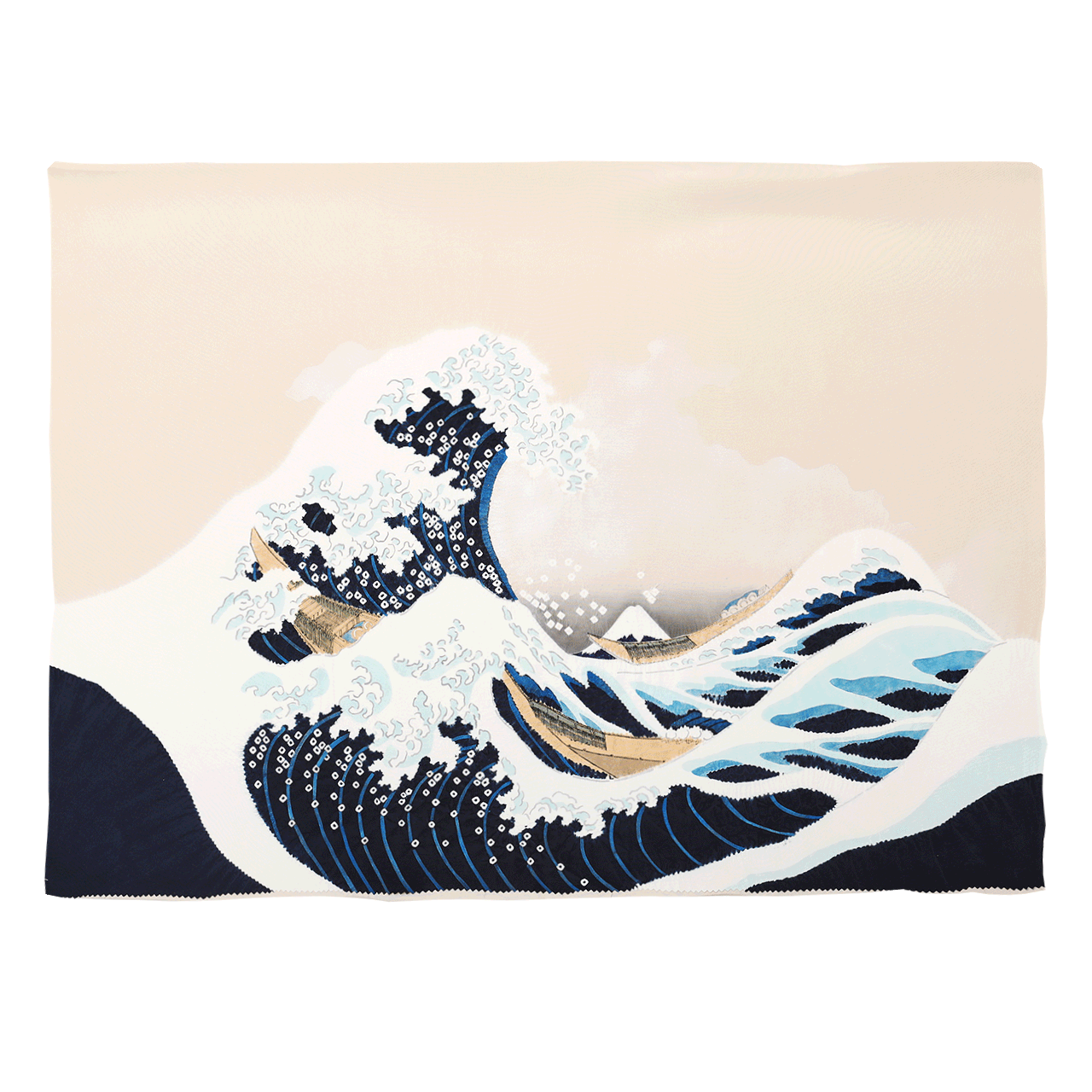

Tsujigahana utilizes Shibori, a manual resist dye technique where fabric is stitched, tied, and dyed to create patterns.

When we consider the evolution of dyeing techniques in parallel with the progression of constructed textiles, we find that the desire to simplify the expression of patterns represented in woven textiles gave birth to embroidery. However, embroidery is hugely time-consuming, and the thin silk fabrics of that time were prone to wrinkling and pilling, making the fabric itself heavier. Consequently, there was a transition towards surface dyeing. Dyeing allowed for lighter and faster production at a lower cost, leading to the emergence and development of the shibori dyeing technique. Dyeing was popularized to mimic patterns created by embroidery, which was originally used to mimic costly woven textiles.

Ogura Atsushis father, established a new artistic style that combined yuzen and shibori, gaining recognition as Oguras Tsujigahana. However, it appears that Ogura himself he was not initially familiar with the historic Tsujigahana. It was during the Taisho and early Showa periods that he received guidance from Inagaki, a famed dyer of the Matsuzakaya Design Department. Inagaki was blown away by his work, asking "Are you creating Tsujigahana without even knowing what Tsujigahana is?" This prompted him father to learn about Tsujigahana for the first time in the Matsuzakaya archives. At that time, Tsujigahana was not widely known, but it gradually gained popularity afterward.

Unlike yuzen, which allows for realistic representations akin to paintings, shibori dyeing is an indirect technique where the pattern lines are stitched tightly and the pattern emerges through immersion in dye. This process results in soft edges and a naturally broad form of the pattern due to the gentle blurred effect.

To express the patterns of Tsujigahana, Japan's unique shibori dyeing techniques known as boshi shibori and rindashi shibori are used.

Boshi Shibori

A technique called Boshi Shibori is used, to leave behind white patterns in the fabric. The fabric is gathered with a thread, and tied around a core of rolled newspaper. It is then covered in plastic, and tied with a string. The fabric will be dyed, leaving the parts covered by the plastic undyed.

The word Boshi means hat, and it got this name as it looks like a hat once worn in the Heian Period.

Rindashi Shibori

This technique is used to dye small parts of the fabric a specific colour. The parts desired to be dyed are tied around a small plastic disc, which almost looks like a big button. The rest of the fabric is wrapped in plastic to avoid it being dyed. This technique takes a huge amount of work, and must be repeated again and again depending on the amount of colors desired.

Houmongi with a design revived from the Edo period.

Inspired by a Houmongi featuring Tachibana (Mandarin Orange) believed to date back to the Edo period, Ogura created a kimono inspired by it over 40 years ago for his wife. He replaced the motif of tachibana for the pattern of plum blossoms. This kimono features vividly dyed blossoms in deep indigo, contrasting with dynamic branches dyed in white and light blue, creating a refreshing impression with its overall cool-toned color scheme.

In shibori, when the space between each motif is small, as in the case of this plum blossom design, it is necessary to dye the fabric in multiple stages, even if using the same color. Due to the numerous plum blossoms and the closely spaced composition, the shibori technique employed here involves multiple stages of rindashi shibori.

Ogura uses acid dyes in the creation of his work. He notes that natural dyes do not provide color stability, leading to color inconsistencies when dyeing in multiple stages. For example, it is said that Toyotomi Hideyoshi's jinbaori (a type of Japanese military garment) underwent three rounds of rindashi shibori dyeing, but due to the use of natural dyes at the time, significant color variations were observed.

Taking inspiration from this plum blossom kimono, Platinum Boy has created a kimono reverting to the Tachibana pattern. Like the plum blossom kimono, this garment features intricate patterns, requiring multiple stages of rindashi shibori dyeing to achieve precise coloration.

Platinum Boy Tsujigahana Houmongi「Tachibana of Spring and Autumn」

【Artist Comment】

Since ancient times, the tachibana (mandarin orange) has been planted in the imperial gardens as a symbol of health and longevity, alongside cherry blossoms. Its fragrant flowers bloom in spring, while its golden fruits ripen from autumn to winter. This artwork incorporates both the spring flowers and the autumn-winter fruits of the tachibana into a single design using shibori, allowing one to enjoy wearing it from autumn through winter and into spring. From a technical perspective, the rindashi shibori technique used for the trunk is particularly challenging. The branches scale the wearer elegantly, with an almost translucent pale yellow background reminiscent of the tachibana itself.

A word from Ogura Atsushi.

"Whether it's a tsujigahana, or a seasonal pattern featuring flowers and butterflies, the sentiment in my work remains the same. I want to share the joyous emotions of each scene with the wearer and those around them.

Unlike western clothing, wearing kimono consists of many layers upon other layers. There is traditionally a kimono, and under kimono, and obi (with coordinating obi-age and obi-jime) and often a haori (jacket). Each of these items each have their lining too, therefore these multiple moving parts are brought together to make a complete look. I wish the wearers of my work enjoy creating outfits with multiple colors and patterns.

Most of my work, both Houmongi and Obi, are dyed usual minimal coloring.I think this makes it easier to coordinate a look, and let you enjoy your item for as long as possible.

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

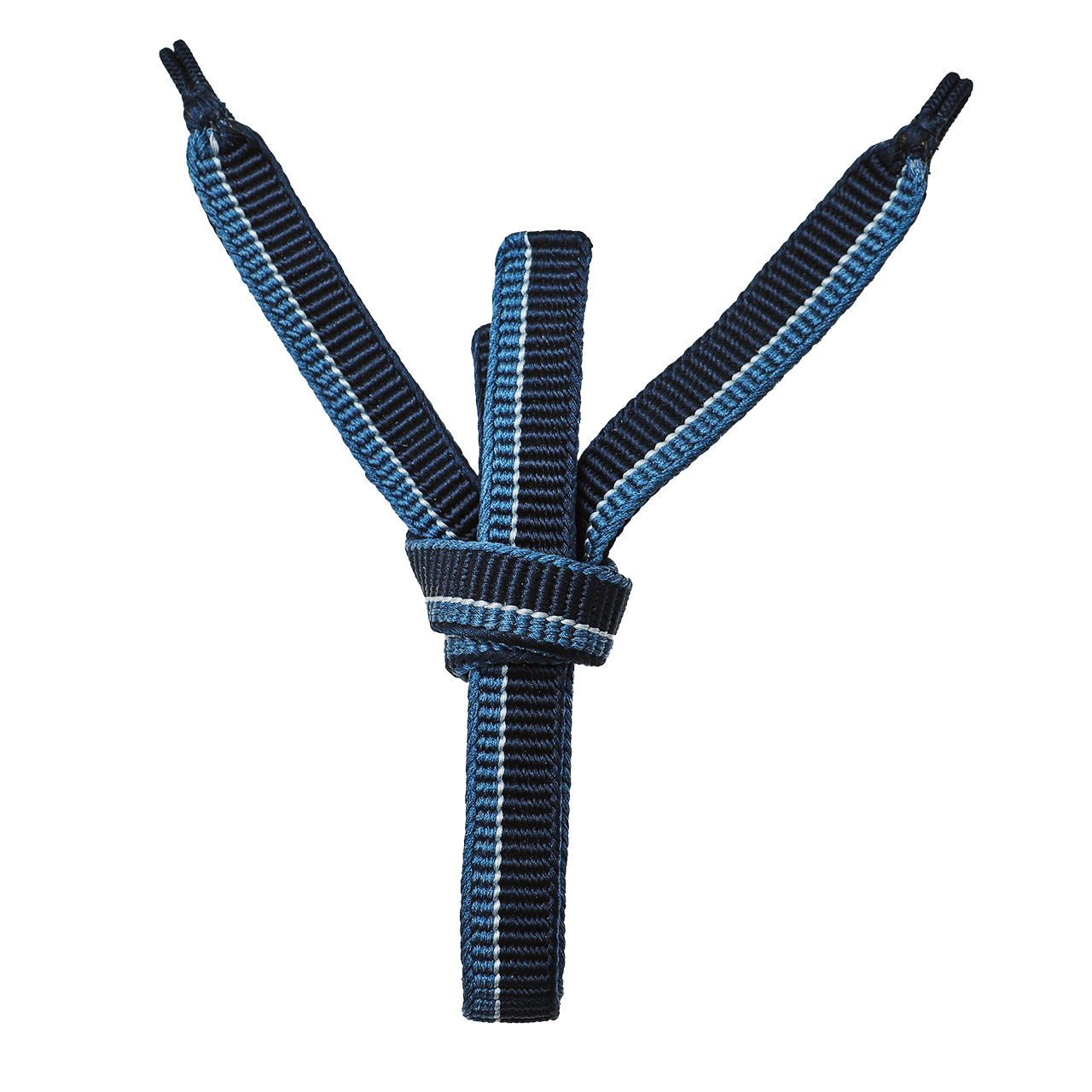

小物

小物

履物

履物

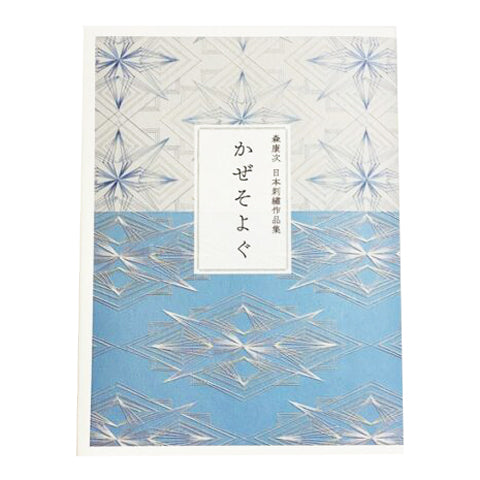

書籍

書籍

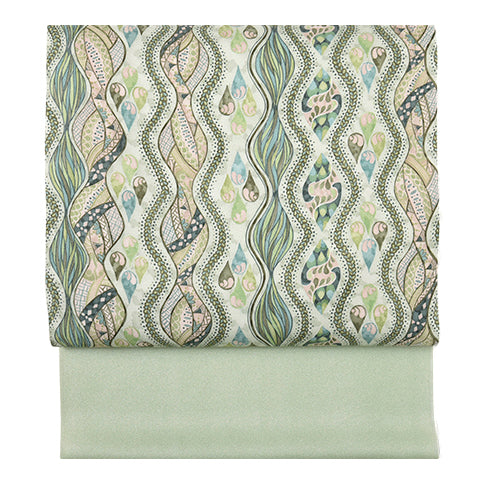

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

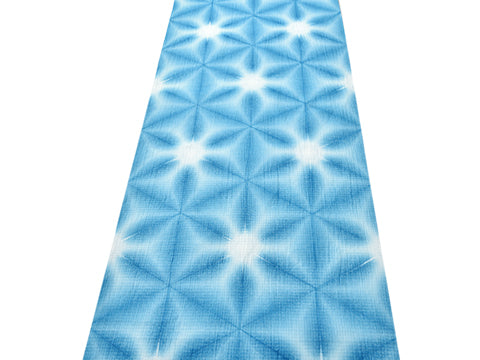

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍