Edo's Popular Profession Rankings: Where Did Weavers, Dyers, and Kimono Merchants Rank? What Were Their Earnings Like?

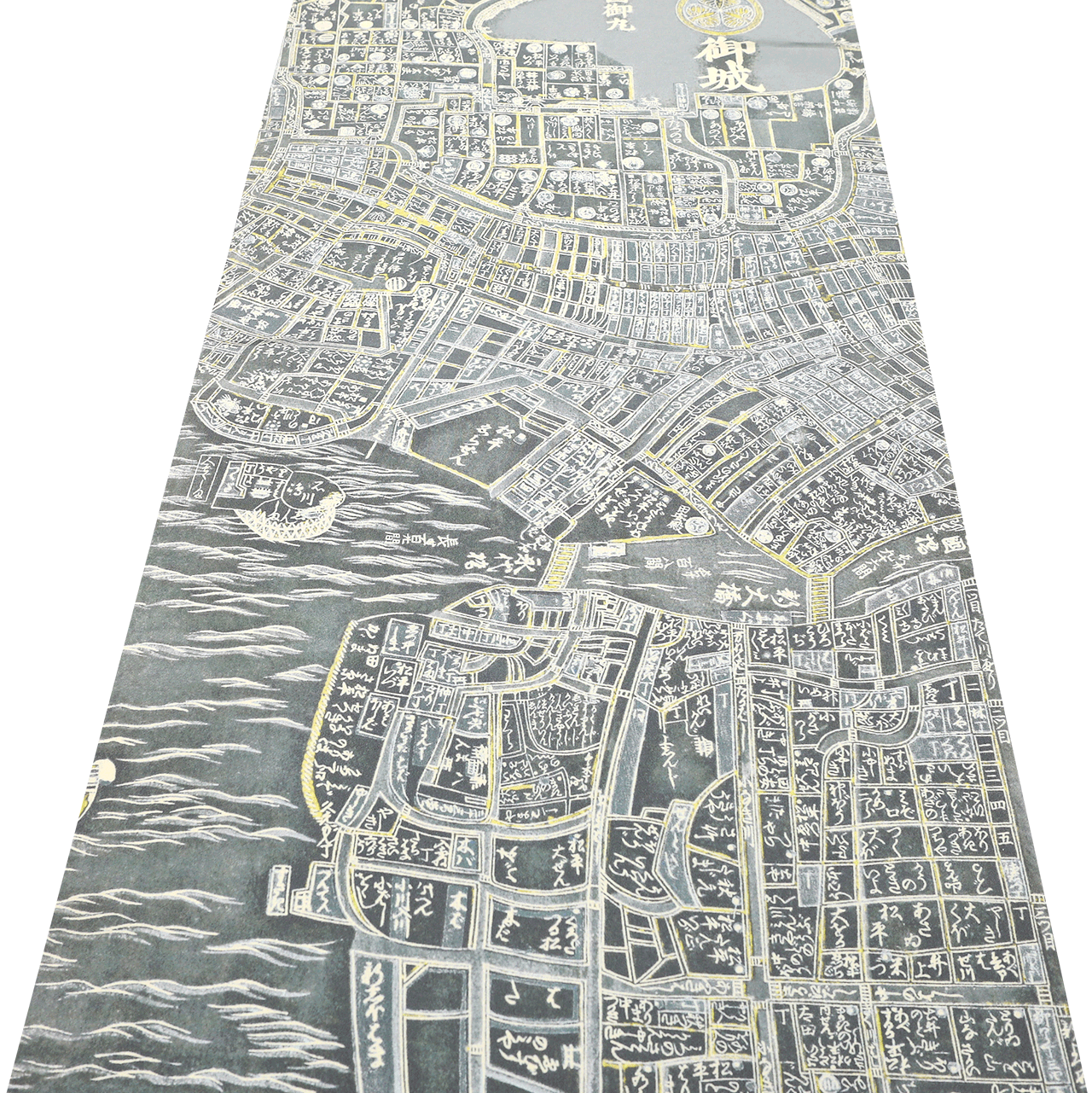

Banzuke, or rankings, were commonly published on various subjects during the Edo period and widely distributed. They provided a glimpse into the best-sellers and trends of the time.

Originally, the word banzuke referred to wooden notice boards that announced the dates of sumo tournaments and listed participating wrestlers along with their ranks. Around the Kyōhō era (1716–1735), these were transitioned to woodblock prints. Eventually, banzuke expanded beyond sumo, leading to the creation of parody banzuke for all sorts of genres. These became a major source of information and entertainment for the people of Edo.

The banzuke format starts with the most popular wrestlers at the top, such as Ozeki, followed by Sekiwake, Komusubi, and Maegashira, with the font size decreasing as the rank lowers. Items or figures that are difficult to categorize into the ranking, such as exceptional or hall-of-fame entries, are noted separately—either alongside the gyoji (referee) or promoter in the center, or as outliers in the margins.

Where did jobs such as kimono sellers, dyers, and weavers place in the ranking?

(Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library)

Let’s dive into the world of craftsmen by taking a closer look at the "Craftsmen Ranking Chart" (諸職人大番附). This fascinating document ranks 140 different types of craftsmen, split into two categories: “Main Trades” (諸職) and “Model Trades” (雛形). Leading the pack in the Main Trades is the carpenter, while the top spot in the Model Trades goes to the swordsmith.

Some professions, however, were considered so prestigious they weren’t ranked at all. For instance, the robe makers (装束師) and crown makers (冠師), responsible for crafting the elegant ceremonial outfits of the imperial court, were given the role of referees. Similarly, firemen, the heroes of Edo’s firefighting efforts, and the craftspeople who made their symbolic matoi banners were listed in a special section, highlighting their elevated status.

When it comes to clothing-related trades, several are ranked prominently. In the Main Trades, weavers come in at 5th place, and embroiderers, who worked on ornate garments, rank 9th. Over in the Model Trades, dyers hold the 5th spot. These high rankings suggest just how much Edo-period people valued the artistry and craftsmanship of their clothing.

Now, let’s talk money. What kind of salaries did these craftspeople earn? Shunsuke Sugano, an expert on Edo culture, explores this in his book, “Edo’s Rich List” (江戸の長者番付). Drawing from a 19th-century document called “Yanagi-an Miscellaneous Notes” (柳庵雑筆), he estimates that the average annual income for craftsmen was equivalent to about ¥4,286,520 in today’s currency. Carpenters, in particular, were well-paid. However, their income was tied to the weather, as they worked on a daily wage basis, and no work meant no pay. This reality gave rise to a grim saying: “You don’t need a blade to kill a carpenter; three days of rain will do the job.”

It’s a vivid reminder of both the importance and the struggles of craftsmen in Edo society!

What did a kimono merchant make yearly?

写真

(Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library)

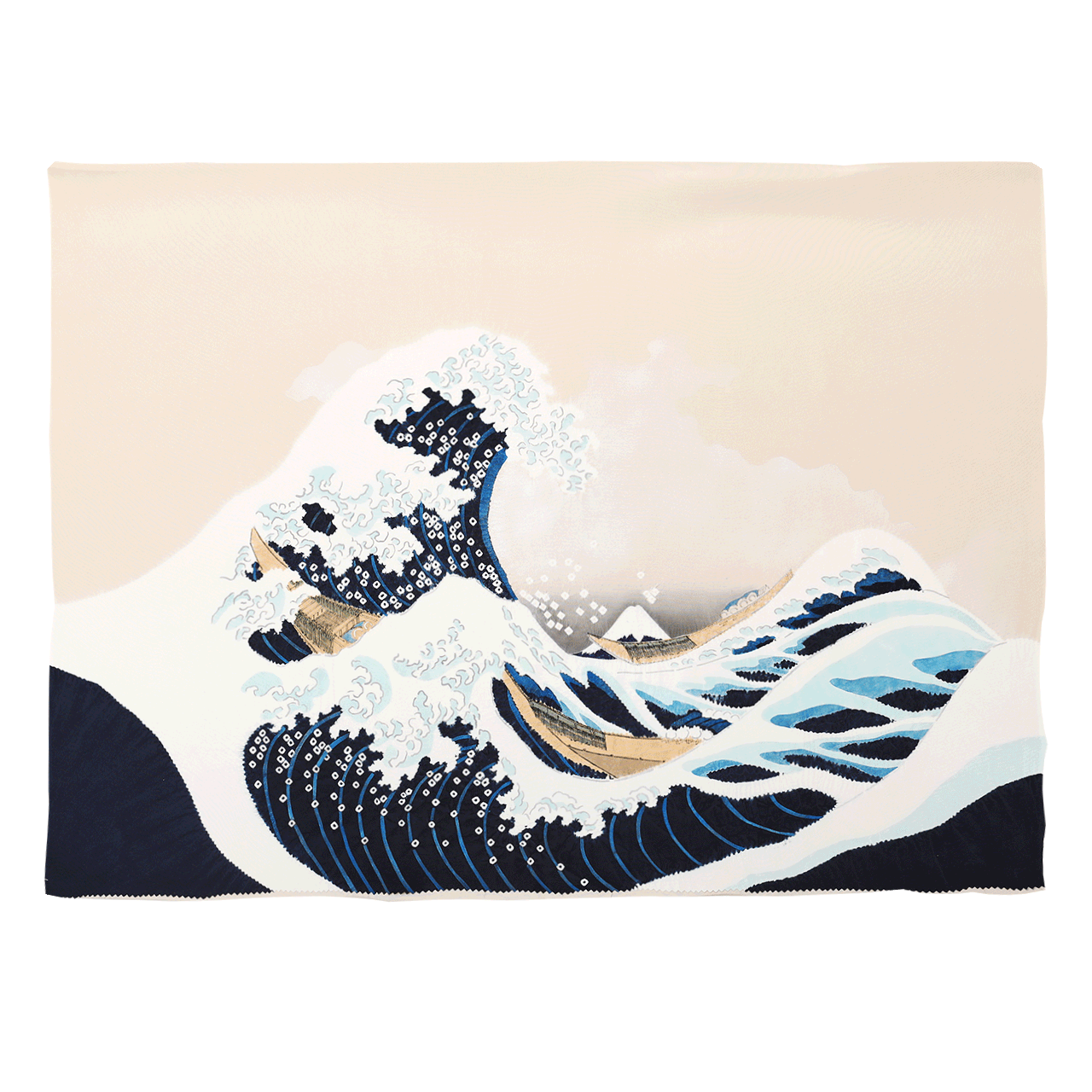

Let’s shift our focus to the merchant rankings. At the top of the list, we have the rice dealers and money changers. Rice dealers dominated Edo-period commerce, accounting for a whopping 38% of overall trade revenue. Money changers, on the other hand, functioned like banks, handling deposits, loans, and issuing currency exchanges. It’s no surprise these trades were incredibly lucrative.

In the realm of clothing-related merchants, cotton fabric dealers (木綿屋) ranked 4th in the eastern region, while used clothing dealers (古手屋) claimed 4th in the western region. Cotton fabric was the go-to material for most commoners, as luxurious silk was often out of reach. Plus, in an era before mass production, textiles in general were extremely valuable as all fabrics were handwoven and hand-dyed. As a result, secondhand clothing was a practical and popular choice, making these merchants essential to everyday life and worthy of their high rankings.

You might wonder why silk merchants (呉服店) didn’t appear in the rankings. Upon closer examination, you’ll find that they were labeled as “Cash Only Drapers” (現銀呉服店) and placed in an exclusive category outside the main list. This term referred to silk merchants who operated strictly on a cash-only basis, highlighting their exclusivity and financial stability. These merchants held a prestigious status, catering to wealthy clients and avoiding the need to offer credit like other businesses. This unique designation underscores their elevated standing in society.

But just how much did these silk merchants earn compared to craftsmen, who we previously learned made an average annual income equivalent to about 4 million yen ($38,000 USD)? Since silk merchants were treated as separate and prestigious, we can safely assume they earned significantly more. Let’s consult Shunsuke Sugano’s “Edo’s Rich List” (江戸の長者番付) once more.

Top 10 Wealth Rankings of Edo

- Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune – ¥129.4 billion

- Daimyo Maeda Nariyasu & Princess Tadayasu – ¥113.5 billion

- Merchant Mitsui Echigoya (Mitsui Hachiroemon) – ¥1.755 billion

- Buddhist Priest of Kan’ei-ji Temple, Prince Rinnoji – ¥737.1 million

- Town Magistrate Ōoka Tadasuke – ¥222.2 million

- Kabuki Actor Nakamura Utaemon III – ¥178.2 million

- Craftsman Ginza Silver Caster, Daikoku Tsuneei – ¥133 million

- Courtesan (Oiran) of Yoshiwara – ¥129.6 million

- Police Chief Hasegawa Heizo – ¥102.3 million

- Elder Lady-in-Waiting of Edo Castle – ¥35.2 million

(Figures adapted to modern-day value from Sugano’s book, "Edo’s Rich List")

Notably, Mitsui Hachiroemon, the head of Mitsui Echigoya, ranked 3rd overall, following only the shogun and a powerful daimyo. His annual income, valued at ¥1.755 billion in today’s terms. This puts his earnings far ahead of notable historical figures like Ōoka Tadasuke, the famous magistrate, and Hasegawa Heizo, the head of the city police.

Of course, this figure reflects the massive success of Mitsui Echigoya, a major business empire, and not every silk merchant enjoyed such staggering wealth. Still, it’s clear that silk trading was one of the most prestigious and lucrative professions of the Edo period, cementing its status as a star occupation of the time.

Courtesans, The Influencers of Edo

As a final highlight, let’s take a look at a special ranking: the most popular courtesans of the Edo period.

【References (All texts in Japanese)】

・『江戸の長者番付 殿様から商人、歌舞伎役者に庶民まで』菅野俊輔 / 青春出版社

・『大江戸番付づくし』石川英輔 / 実業之日本社

・『大江戸まる見え番付ランキング』監修・小林信也 / Gakken

*Text translated to English from the original Japanese

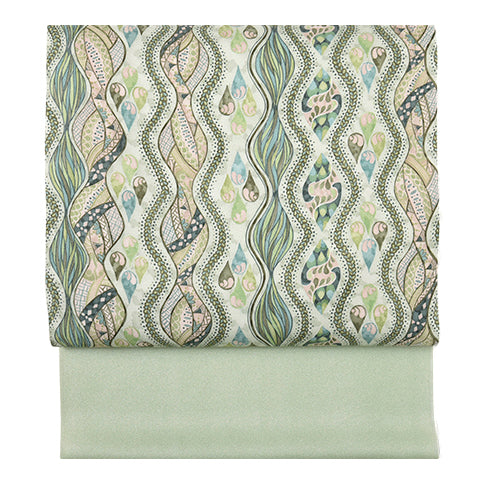

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

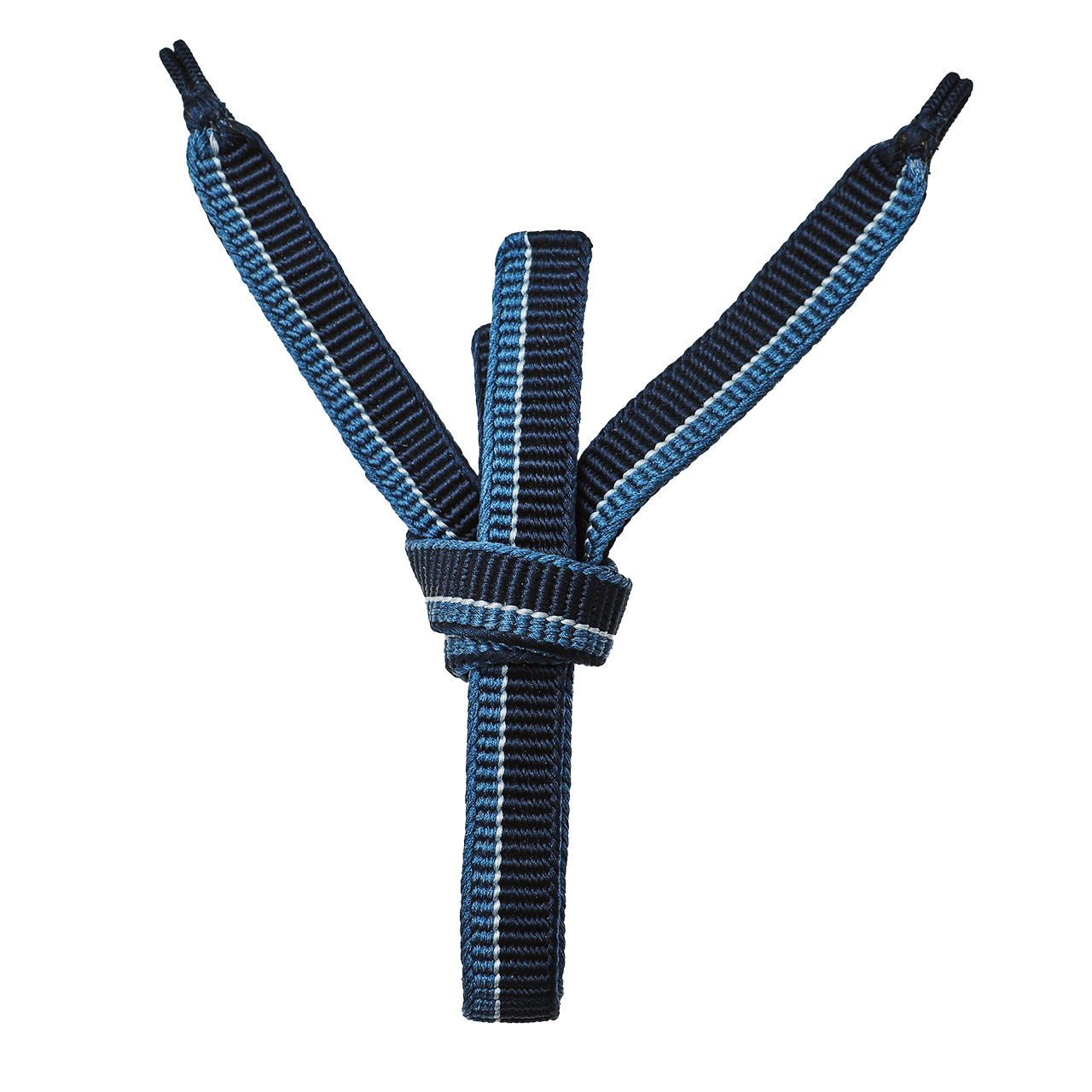

小物

小物

履物

履物

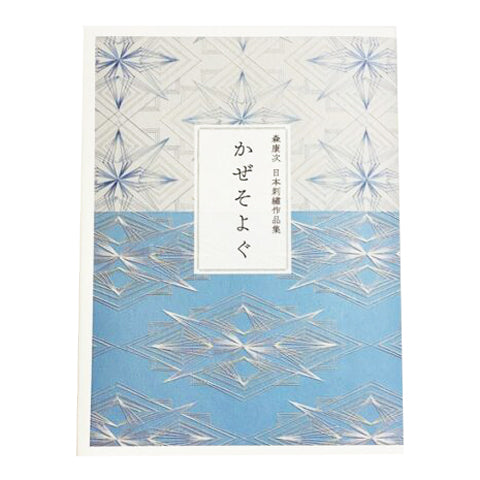

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

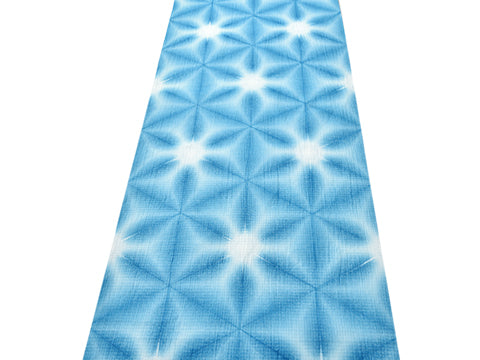

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍

(Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library)

(Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library)