Furoshiki, a traditional wrapping cloth, has been cherished in Japanese daily life for centuries. While its classic use involves wrapping items, it also serves as a versatile item with various applications, such as a placemat, an eco-friendly bag, or even as a decoration. In this article we unwrap the history of furoshiki and explore the reasons behind its enduring appeal.

The Origins of Furoshiki

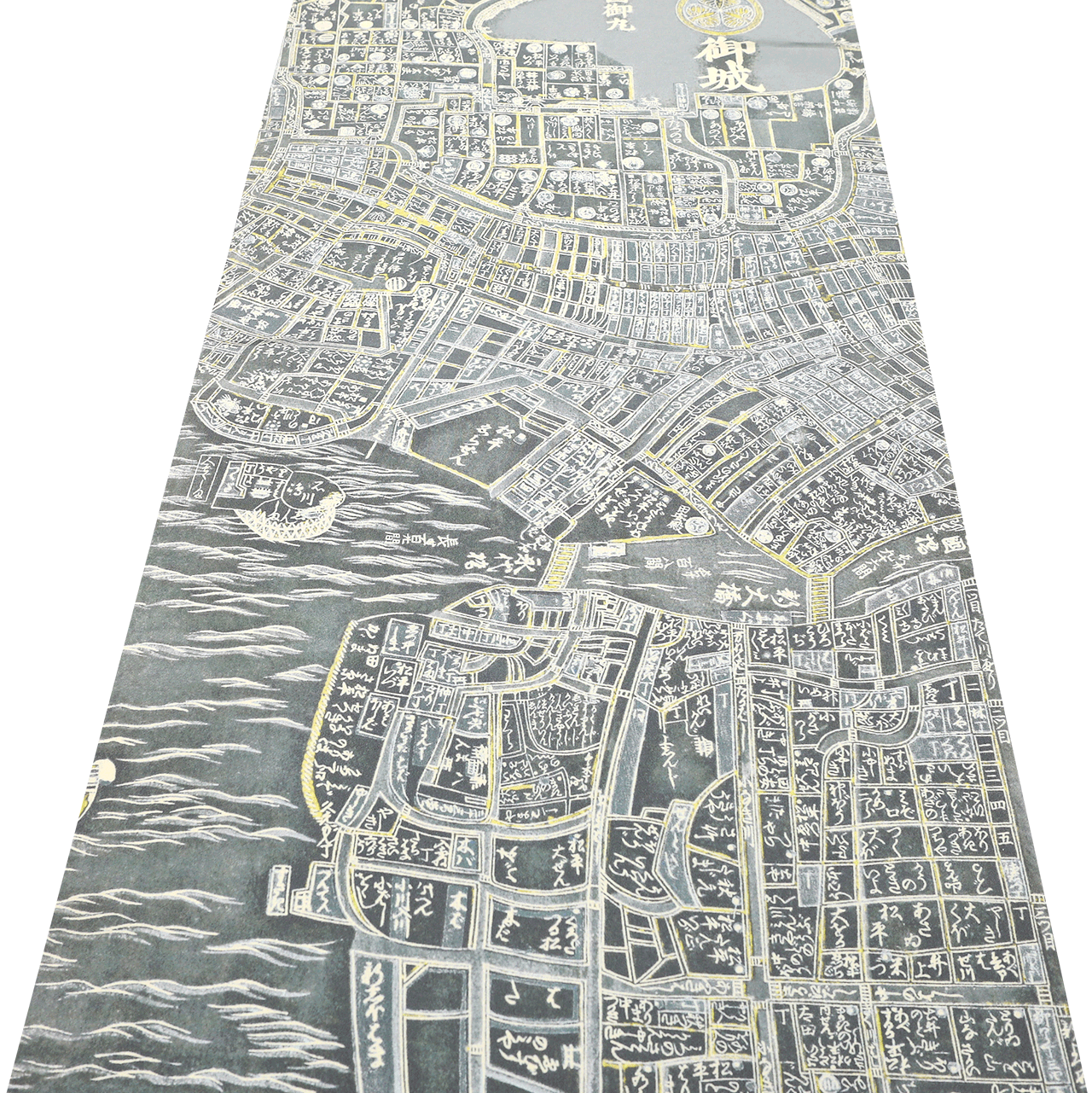

Cloths used specifically for wrapping have existed since ancient times, with examples discovered at various historical sites, including the Shosoin Repository. However, the term furoshiki originated in the Muromachi period. It is said to have started when the daimyo attendants of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu used a cloth bearing their family crests to wrap their belongings while using the bathhouse called Ōyudono, which Yoshimitsu had built. To avoid mixing up their clothing with others, they wrapped their items and then used the cloth as a mat to change on after bathing. At the time, such cloths were known as hiratsutsumi (flat wrapping), but over time, the name "furoshiki" became widely adopted.

Nishikawa Sukenobu / National Diet Library

In the Edo period, the culture of furoshiki spread widely among the general public with the emergence of sento (public bathhouses). Over time, its uses expanded as they were practical for carrying a wide range of items. Furoshiki were also used as a tool in disaster preparedness, placed under ones futon so that essential belongings could be quickly wrapped and carried in case of a fire (which was a common thread in edo). Its versatility, allowing it to adapt to a wide variety of uses, made it an indispensable item.

Moreover, furoshiki played a role in advertising and promotion. A famous example involves Shimomura Hikoemon, the founder of what is now Daimaru Department Store. Originally from Kyoto, Shimomura sought to establish a successful business in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) despite having no connections. To make a strong first impression, he ordered a large number of furoshiki dyed in a vibrant green and emblazoned each one with the “Daimaru” trademark. He used these furoshiki to wrap products sent to Edo. Along the journey, the striking furoshiki caught the attention of people along the highways, and upon arrival in Edo, the sight of shop assistants carrying goods wrapped in these eye-catching cloths drew the notice of fashion conscious locals. It is said that the bold furoshiki quickly became the talk of the town.

Beyond Wrapping: The Versatility of Furoshiki

In the Muromachi period, furoshiki began as an essential item for bathing. Over time, from the Edo period onward, they evolved into everyday items used in a wide range of situations, continuing to the present day. While they may seem like a uniquely Japanese cultural artifact, similar cloths can actually be found in various parts of the world. For example, in Guatemala, there is a traditional multipurpose cloth called sute. Said to have over 100 uses, such as carrying goods and providing sun protection, it is often passed down from mothers to their children. In Turkey, a cloth resembling the furoshiki is used for wrapping clothes and toiletries when visiting public baths. However, even though these are all single pieces of cloth, their materials and applications vary somewhat depending on the climate, religion, and other cultural factors of each region.

So, what does the furoshiki mean to the Japanese, and why is it still recognized as an element of Japanese culture both domestically and internationally? One clue to unraveling this question lies in the word "tsutsumu" (to wrap).

The term tsutsumu itself has ancient roots and appears in several poems within the Manyoshu, Japan's oldest anthology of poetry.

Man'yōshū - Hamaomi Shimizu / National Diet Library

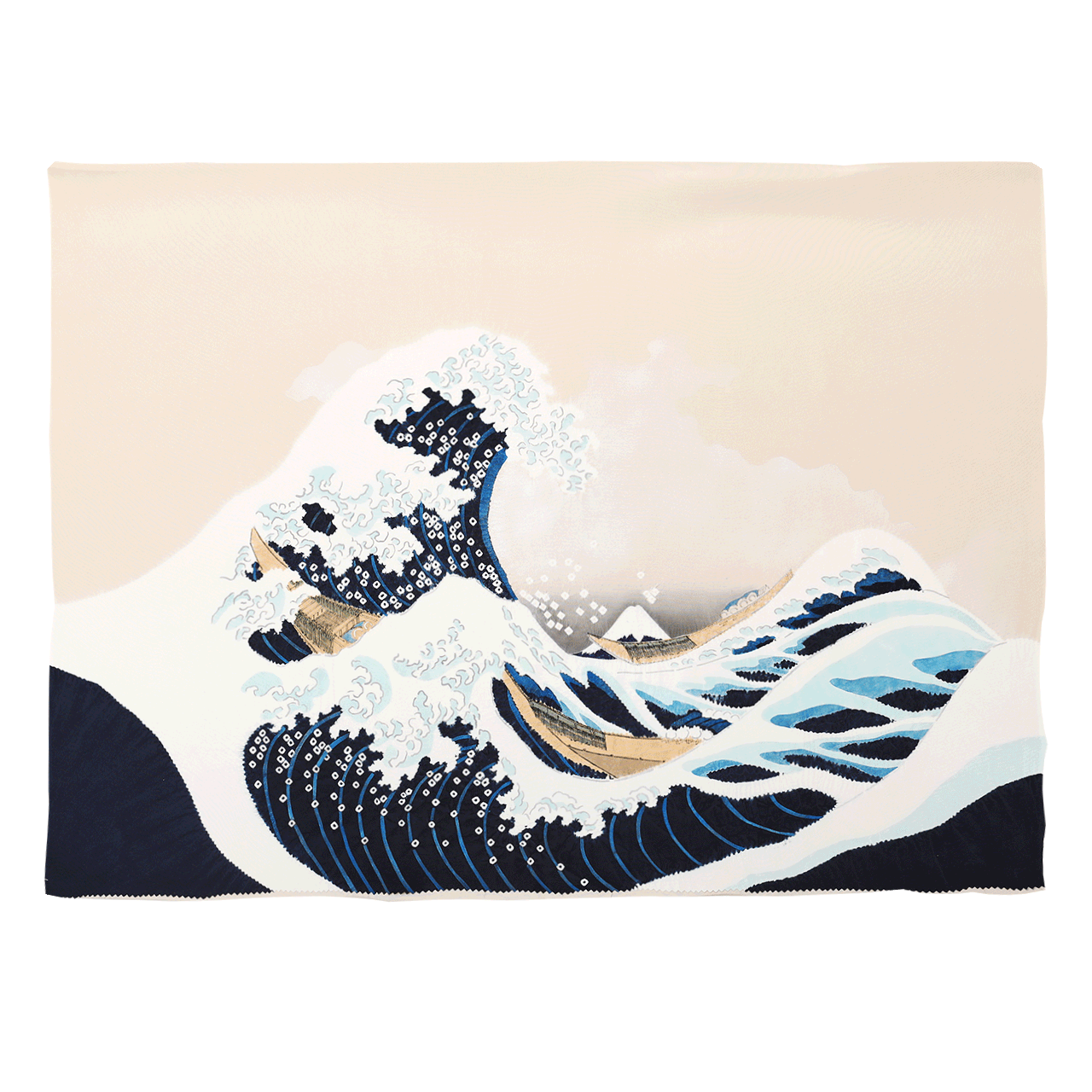

“The white waves off the coast of the Ise Sea are as beautiful as flowers. If only I could wrap these stunning waves in a pouch and take them home as a gift for my wife.”

(Man'yōshū, Volume 3)

“The body of water called ‘Senoumi’ is embraced by this mountain, just as the sea is enveloped by the towering Mount Fuji, which stands so grandly.”

(Man'yōshū, Volume 3, Interlude Poem)

As seen here, these examples reflect a usage that remains relatable and understandable even today. At the same time, there are also poems with expressions like the following:

“"I wish it would rain. If it rained, you wouldn’t be able to go outside, and I could spend the whole day indoors with you."

(Man'yōshū, Volume 4)

(translated from the original Japanese)

In the case of this poem, the word "tsutsumu" is used with the meaning of "to block" or "to shield." While the character 包 (tsutsumu, "to wrap") is commonly used today, in ancient times, characters such as 裹, 障, 簾, and 袋 were also employed. Beyond the meanings of "to wrap" or "to envelop," the word "tsutsumu" also carried connotations of "to restrain," "to surround," "to conceal," and "to shield." This diverse range of meanings extended not only to language but also to actions.

By the Heian period, customs resembling the modern use of fukusa (decorative wrapping cloths) were already in practice. Gifts were wrapped in cloth to protect them from impurity and malevolent forces. Additionally, in Section 46 of The Pillow Book (Makura no Sōshi), it is described how guumi (silverberry) and chrysanthemums were wrapped in cloth and hung from pillars or mosquito net stands to ward off evil spirits. This suggests that the act of wrapping was not merely for enclosing objects but also served as a means of shielding the contents from external threats.

In his work The Cultural History of Things and People 20: Wrapping, scholar Iwao Nukata observes:

"The concept of 'wrapping' is not only deeply integrated into our practical lives but has also surprisingly profound roots in our spiritual and cultural dimensions."

At the time, cloths closely associated with the act of wrapping (such as momen-nuno, cotton cloth) were often offerings to the gods. It is possible that people of that era sensed a certain mystical nuance in the act of wrapping.

The Culture of 'Wrapping' as Seen in Edo Manners

The practice of maintaining harmony for people, objects, and events through wrapping evolved into gestures by the Edo period. Katsunori Ishiyama, in his book “Things Go Better When You Wrap Them Just a Bit,” states that the ancient “culture of wrapping” is reflected in Edo customs. These customs were wisdom born out of the necessity for peaceful coexistence in Edo, a metropolis of one million residents where samurai and townsfolk of differing social statuses lived side by side without conflict.

Specific examples include gestures like "kobushi-koshi ukase": standing slightly to make room for others boarding a boat, the idea of avoiding "time theft" (unannounced visits or last-minute changes that waste another's time), and "the teaching of three omissions" in communal baths, which discouraged asking about age, profession, or social status, promoting equality. While debate exists about whether these practices were truly widespread, the tendency to avoid explicit confrontation and instead “wrap” others with a metaphorical cloth of consideration to prevent trouble and foster harmony resonates with the modern image of Japanese society.

The furoshiki, with its origins rooted in practicality and its evolution into a cultural symbol, embodies the Japanese philosophy of harmony and adaptability. Beyond its functionality, it reflects the enduring wisdom of wrapping—whether to protect, preserve, or create connections between people and objects. Today, as sustainability becomes a global priority, the furoshiki’s versatility and eco-friendly nature resonate more than ever. By embracing this timeless tradition, we not only honor its history but also carry forward its spirit of mindful living into the modern world.

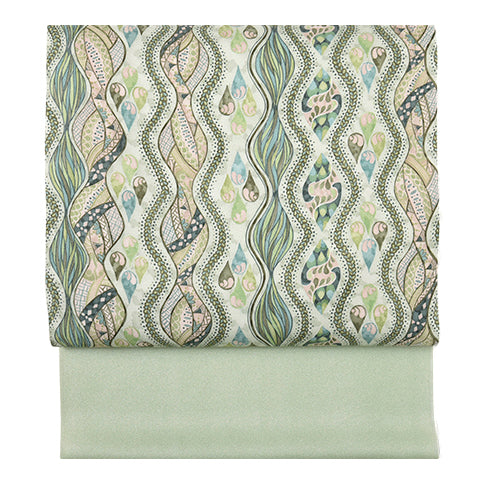

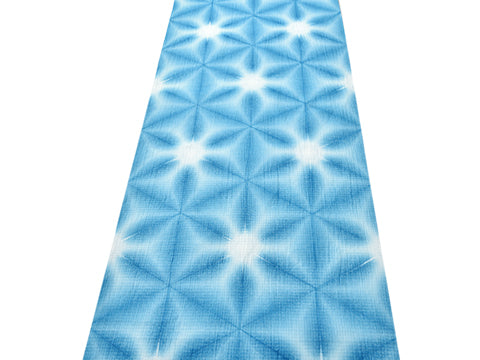

Take a look at our all of our furoshiki

References (Japanese only)

『ものと人間の文化史20 包み』額田巌 / 法政大学出版局

『飛鳥から平安時代における「包み」の文化ー「風呂敷」の語源とその前史ー』深澤琴絵・他

『ちょっと包んだほうが人間関係はうまくいく』石山勝規 / 合同出版

『ふろしきの歴史』宮井株式会社

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

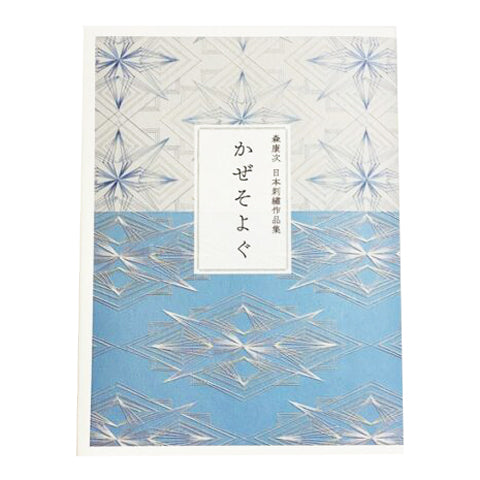

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍