In the transitional period between tradition and modernization in Japan, a unique clothing culture emerged where traditional Japanese attire and Western clothing coexisted. While Western clothing became more prevalent in public spheres, such as military uniforms and other official settings, many people, regardless of gender, still wore traditional Japanese clothing in their daily lives. So, how did people specifically enjoy traditional Japanese clothing as everyday wear? This time, we will focus on men's traditional Japanese attire and summarize the key points of stylish coordination from that era.

1. Every decent man should...

The pinnacle of mens style, Saigo-gara Oshima Tsumugi

“‘Oshima on a man is truly so becoming, You simply must buy a set. Not just in dribs and drabs, the whole set all at once, Ippiki(1*)! . You really must buy one by this fall. For men, nothing is better than Oshima!.’

This is an excerpt from an exchange between the protagonist, Jōkichi, and his wife in Kan Kikuchi's book 'The Story of Making Ōshima.'

From the 1880s to the early Showa period, Oshima Tsumugi was the envy of many men. It was said to be popular because it was comfortable, durable, wrinkle-resistant, and featured chic colors and timeless patterns. However, due to its prohibitive cost, it was unnatainable to many. Wearing Oshima Tsumugi in a matching haori and kimono ensemble was a status symbol for men. In the same book, there is a scene another scene where...

‘What! You’re wearing an Ōshima,’ Jōkichi couldn't help but exclaim in admiration. Sugino, who had a proud look on his face, responded, ‘How about it, splendid, isn’t it?’ Jōkichi glowerd with envy.

Besides Ōshima Tsumugi, other popular silk fabrics included Yūki Tsumugi and Meisen. Among cotton fabrics, Futagojima (in the Meiji period) and Kurume Kasuri (from the Taisho period to the early Showa period) were popular.

※1) Ippiki (一疋) is a bolt of cloth with enough fabric to make not just a kimono but also a haori. A kimono and haori of the same cloth is often called an ensemble (アンサンブル), and owning an ensemble was seen as a status symbol.

2. An Overcoat, THE essential winter item.

Since the Meiji era, coats rapidly became popular among all men, including men who wore kimono as well as those who wore western clothes. For those who wore kimono, styles like the Inverness coats, double-breasted coats, and tonbi coats were trendy. Newspapers of the time reported, "No man is without a double-breasted coat; everyone is buying them for not only warmth but also to hide worn-out clothes" (Hochi, January 29, Meiji 29). By the Taisho era, coats with fur collars began to appear. These were mainly worn by the wealthy. In contrast, clerks, small merchants, and craftsmen tended to wear lighter, more comfortable coats with square or funnel sleeves.

Additionally, there was an item known as the aka-getto(赤ゲット),a red cloak-like garment. This red blanket was worn by people who came to Tokyo from the countryside during the Meiji era, serving as a substitute for a coat. Rather than being considered fashionable, it was seen as a symbol of being unsophisticated or provincial.

3.Hats were worn by not only men, but boys too!?

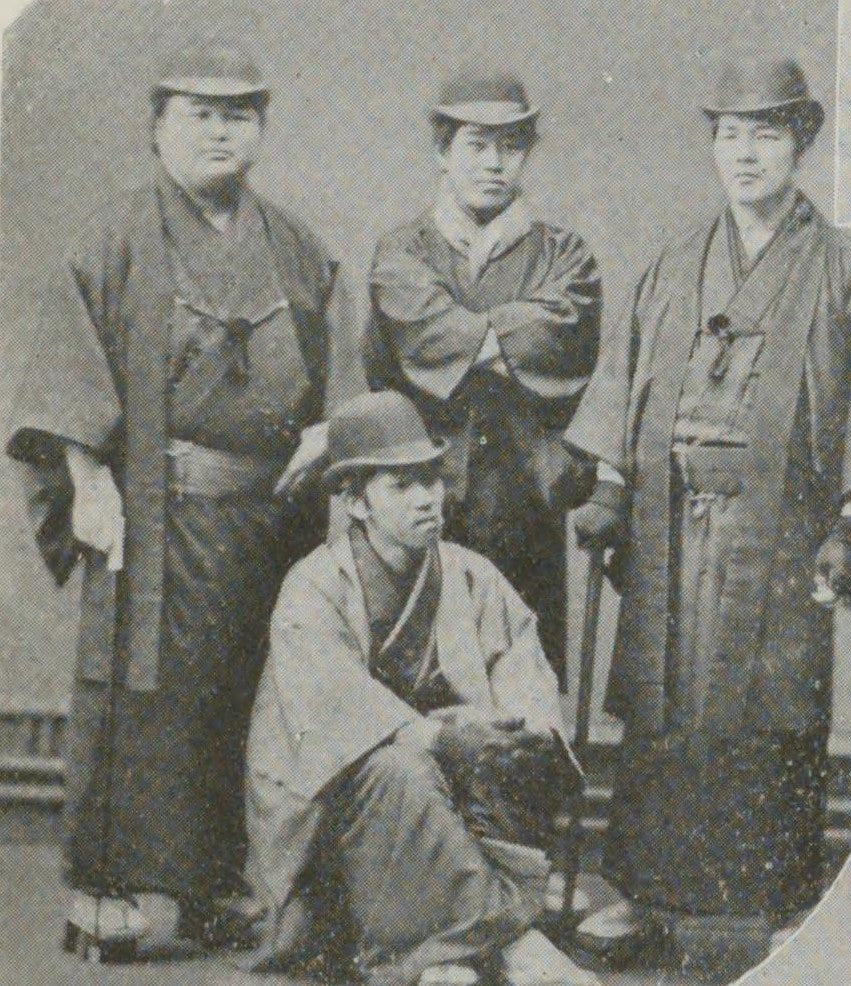

In the Meiji to early Showa period, hats were an essential item for men. In the early Meiji era, many men who resisted cutting their traditional topknots often wore hats to cover their heads. Gradually, hats became an indispensable part of proper grooming. Many men, from students to adults, wore them eagerly. White-collar men, especially before the war, were particularly fond of their hats, wearing them even when they went next door to borrow a telephone.

August 1918 / National Diet Library

Among the many types of hats, the bowler hat proved popular in the beggining of Meiji, and in Taisho the fedora and flat cap took over, and were often seen paired with kimono.

A View of Tokyo Customs (東京風俗志. 中) / National Diet Library

In the summer, Boater and Panama hats were favoured. Straw boaters were light in colour so dirtied easily. Despite this, they were cheap, and it is said that many men used them almost disposibly, wearing a new one each day.

The Panama hat, originally a traditional headwear of Ecuadorian indigenous people, gained global popularity by the late 19th century. It became a fashionable and expensive hat in Japan as well. There's an anecdote that Natsume Soseki purchased his long-desired Panama hat with the manuscript fee from "I Am a Cat."

4.The walking stick took over as the gentleman's accessory of choice

When it comes to canes, some people today might primarily associate them with walking aids for elderly individuals with mobility issues. However, during the Meiji to early Showa era, canes were essential fashion items that accentuated sophistication. They were adopted by gentlemen regardless of whether they wore Japanese or Western clothing. Notable figures such as Ryunosuke Akutagawa and former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida were known enthusiasts of canes.

Takahashi Korekiyojiten / National Diet Library

Did you know that there was once a cane with a concealed sword blade in its sheath, used for self-defense? After the Sword Abolishment Edict, some former samurai felt uneasy going outside without any blade, so they used these canes. It might seem quite dangerous by modern standards, but swords held significant cultural and psychological importance for samurai.

5. No watches with kimono please

These days, wristwatches are the norm for mens time pieces, but during the Meiji to early Showa period, pocket watches fulfilled the role of time keeping. In Japan, the adoption of the solar calendar in 1873 led to the introduction of a 24-hour system, and by around 1887, wall clocks were widespread even in rural areas. However, portable pocket watches were limited to a few affluent individuals, and they were objects of aspiration for many men.

Timepiece / National Diet Library

When wearing kimono, pocket watches were often carried by tucking them into the obi or placing them inside the kimono sleeve, leading to them being referred to as "袂時計" (sleeve watches). While wristwatches began spreading worldwide following advancements in Swiss technology from the 1910s onwards, they also made their way into Japan. However, enthusiasts of purely Japanese aesthetics often believed that bracelets and similar Western accessories were discordant with kimono, thus preferring pocket watches as the timepiece for traditional attire.

During the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods, men skillfully blended Western-style accessories with kimono, creating a sophisticated fusion of nostalgia and trends. Learning from the sensibilities of men from that era, why not consider incorporating traditional Japanese clothing into your daily wardrobe? It could open a new door to fashion for you.

References (Japanese only)

・『日本人のすがたと暮らし 明治・大正・昭和前期の身装』大丸弘・高橋晴子(三元社)

・『服装の歴史』高田倭男(中央公論社)

・『日本衣服史』増田美子(吉川弘文館)

・『大島が出来る話』菊池寛

・『3.帽子の変遷』モーレン鈴木

・双子織り/機織のご紹介(蕨双子織HP)

・夏目漱石、『吾輩は猫である』の原稿料で念願のパナマ帽を買う。【日めくり漱石/7月2日】 / サライ(小学館)

・日本で初めてステッキを持った人とは?文豪も愛したステッキの歴史(タカゲンHP)

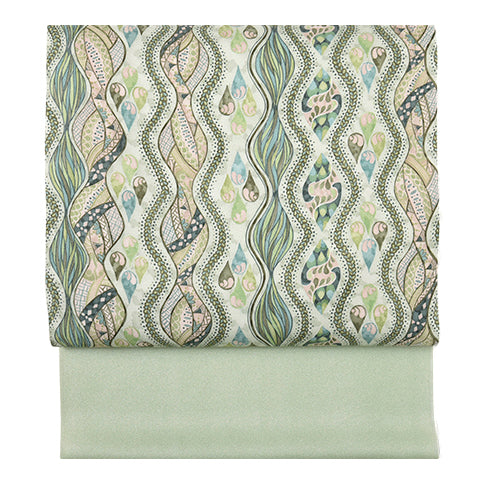

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

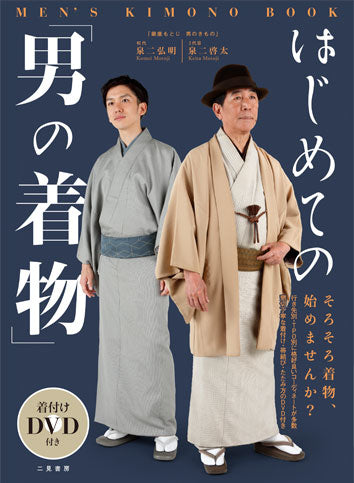

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

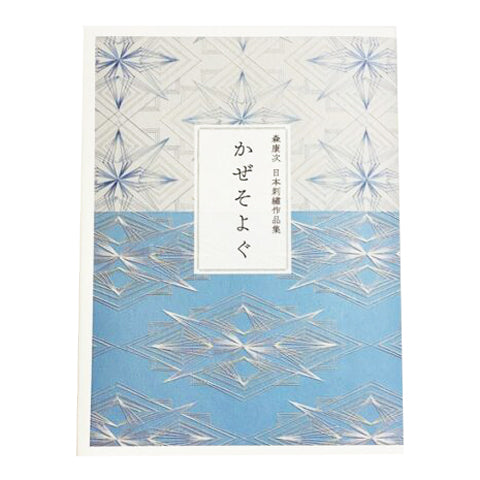

書籍

書籍