ASANO, Hirotaka in his atelier.

[Photo:SHIOKAWA, Yuya]

Ahead of our December Event, Staff from Ginza Motoji visited the workshop Shokuraku Asano, of Asano Hirotaka in Nishijin, Kyoto.

「Enjoy, Weaving」The theme for the brand is to enjoy the possibilities of weaving.

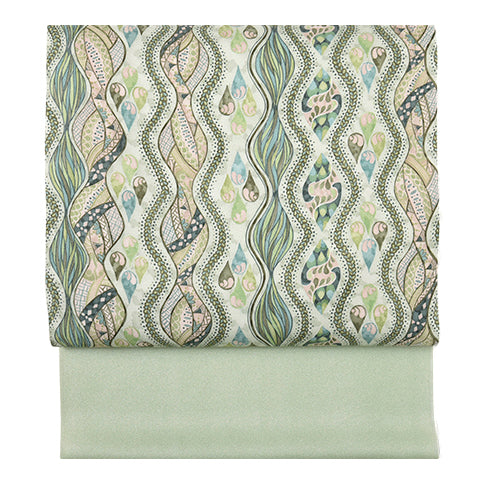

Recent works displayed in the showroom. Up until now, Shokuraku Asano has designed over 4,000 unique patterns.

Founded in 1980 with the concept of "Enjoying Weaving," Shokuraku Asano is a weaving brand with a remarkable legacy. Including its predecessor, "Asano Oriya," the brand marks its 100th anniversary in 2024.

In 2005, we hosted our first Shokuraku Asano event, and this wear will be our 16th exhibition. With stunningly refined designs and unparalleled ease of use, Shokuraku Asano's works enjoy immense popularity. In fact, our staff rely on them so often that we've coined the phrase "When in doubt, Shokuraku"

With just one of Asano's obi, a tsumugi kimono transforms into a polished look, classical yawarakamono kimono pieces take on a modern feel, and forlorn inherited kimonos gain a contemporary flair. Shokuraku obi possess a unique power to harmonize kimonos with today’s urban landscapes, striking a balance that feels just right.

[Left] light, casual leaning tsukesage kimono is paired with a Shokuraku Nagoya obi. [Right} A Shokuraku obi adds interest to this simple Oshima kimono. Limited colors gives you free reign with your obi-age and obi-jime.

[Left] Shokuraku obi worn with a casual tsumugi [Right] With an omeshi kimono. Just add a Haori and this look is ready to be worn in a semi-formal scene.

Asano often says, “Beauty is not inherent to the object itself but lies in the relationship between objects.” This philosophy aligns with the uniquely Japanese aesthetic described by Junichiro Tanizaki in In Praise of Shadows. Asano-san places this sensibility at the very core of their craftsmanship.

“It’s meaningless to aim for perfection in the obi alone. The obi exists in harmony with the kimono, in combination with the obiage and obijime, and above all, it must enhance the beauty of the wearer. The key is for each element to complement the others.”

For this reason, Asano-san always keeps in mind the importance of leaving “space” for other elements to blend in. They carefully design their weaves with an emphasis on restraint in the number of colors, the base fabric and texture that support the patterns, and the subtle nuances. The reason Oraku Asano’s obi are so easy to coordinate is that they are meticulously crafted with coordination in mind from the very beginning.

In Praise of Shadows (In'ei Raisan, 1933) by Junichiro Tanizaki: The author explores the idea that “beauty does not reside in the object itself, but in the interplay of shadows (light and dark) created between objects.” This work identifies the distinct beauty of Japan within its appreciation for the subtle aesthetics of shadow and light.

Tradition was once avant-garde.

Asano’s workshop houses an extensive archive, meticulously curated over time together with his father. The collection includes design books, magazines, paintings, art exhibition posters, as well as various materials such as whetstones, bamboo chopsticks, and calligraphy brushes. It is both vast and impeccably organized.

“It wasn’t like today, where you can just search the internet and instantly find answers. Back then, we had no choice but to collect physical materials ourselves.”

Magazines were carefully cut and organized into scrapbooks, serving as a source of design inspiration. With the mindset of creating an original Shokuraku Asano database, he approaches this task almost like a small-scale cottage industry.

"If you were born in again in 2024, would you collect as much?"

He laughed and replied, "Probably not to this extent. Analog collections take up a lot of space, and book spines inevitably get damaged."

However, he noted that many of the items in the collection are now impossible to obtain, and there is undeniable value in hard materials that you can't find through online searches.

“Today’s search methods are all about how quickly you can reach your goal, but with analog methods, you often stumble upon unexpected discoveries—'Oh, this is interesting too!'—along the way. Those detours can prove useful later on. The journey to the answer is much richer.”

Among the collection are textiles from civilizations over 1,000 years old, including the Coptic and Persian cultures.

“We often think that traditional textiles are valuable simply because they have history, but that’s not the case. When they were first created, they carried an unprecedented boldness and beauty—a kind of ‘How about this?’ attitude toward the world. They were avant-garde in their time. It’s because people cherished and preserved them that they still exist 1,200 years later and hold such value.”

Whether drawing inspiration from designs of the Shosoin or maki-e lacquerware, Asano-san places great importance on infusing creations with the same energy and boldness—the “How about this?” spirit—that the original makers imbued their works with when they were first conceived. At the same time, they are always mindful of refining the designs to be more beautiful and suited to contemporary attire.

When asked what “sophistication” means in today’s world, Asano-san paused for a moment before replying, “I think it’s about lightness and elegance. Also, luster and a sense of quality.”

Not “綺麗” or “キレイ,” but the soft, flowing “きれい” in hiragana. When Chinese characters were introduced to Japan, hiragana was born, leading to the development of Japan’s unique culture. Hiragana itself embodies the Japanese aesthetic, with its sense of spaciousness, flexibility, and light rhythm.

Through Asano’s unique lens, the world’s diverse aesthetics transform as if evolving from kanji to hiragana. These inspirations take shape as the light, elegant beauty of practical art—kimonos and obi—delivered into the hands of wearers today.

- Sezession -

Asano embarked on a journey to Vienna this summer in search of inspiration. From the moment he arrived early in the morning and entered the Albertina Museum, formerly the residence of the Habsburgs, he was captivated by everything he saw.

Drawing inspiration from Klimt’s decorative murals, the laurel dome of the Secession Building, and the Belvedere Palace, Asano-san absorbed the energy of the early 1900s and infused it into his new creations.

A look at the collection "Sezession".

Nagoya Obi - Klimt Vision

"Belgian entrepreneur Adolphe Stoclet commissioned a mural for his living room, featuring Klimt’s iconic female figure in Expectation. The triangular scale pattern depicted on her clothing served as the inspiration for this design, incorporating a shifting combination of ground patterns in a stepwise arrangement.

The triangular motif is said to have been favored by the Wiener Werkstätte, and one can sense echoes of Japan’s cultural influence, such as the flowing water patterns of the Rinpa school or the scale motifs found in Noh costumes. This reflects the impact of Japonisme on their aesthetic sensibilities."

Nagoya Obi - Klimt Floral Pattern

"The piece I most wanted to see in person was Klimt’s decorative murals at the Vienna Museum of Art History, themed around ancient Greece, ancient Egypt, and classical Italian art. These works inspired the motif for the patterns on the garments worn by the saintly figures depicted.

The original patterns were based on damask weaving, which came to Italy influenced by the Middle East. The design emphasizes a harmonious and well-balanced beauty, with a striking contrast between the base color and ivory, further accentuated by gold thread and foil."

Nagoya Obi - Parquet

"The flooring at the Albertina Museum features a variety of woods arranged using marquetry techniques, creating an intricate inlay-like effect. Inspired by the arabesque patterns found in the flooring, the design has been reinterpreted.

The fabric is woven with a base structure of shusuji (satin ground) and employs the baigoe technique, emphasizing variations in weave structure and color to represent the different textures of the materials. The term parquet refers to decorative flooring made by arranging wood in a mosaic-like marquetry pattern, and this artistry serves as the foundation for this woven design."

Kaku Obi - Quince

The design is inspired by the craftsmanship and design of the Wiener Werkstätte. It reflects the influence of layouts reminiscent of Middle Eastern window frames, but its impression also aligns with the traditional Japanese quince pattern.

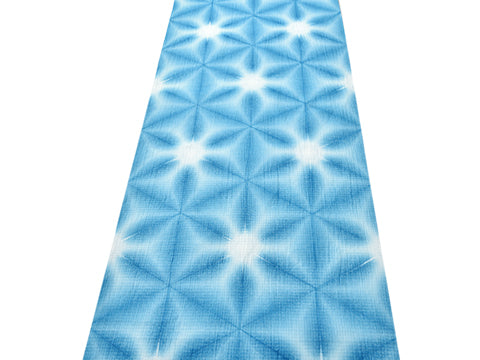

Kaku Obi - Stardust

This design captures the interplay of complex expressions and diamond-shaped patterns subtly appearing in Klimt's paintings, expressed through weaving. The weave combines three colors that intricately intersect, creating a dynamic effect where the diamond patterns emerge and shift as focal points. The color combinations are more varied than in previous works, offering enhanced coordination possibilities with kimono.

The design features three randomly arranged base colors, with one of these colors used to weave the diamond motifs. For women’s items, the diamonds are made more prominent, while for men’s items, the colors are subdued to achieve a sophisticated and understated finish.

Komon Kimono - Stencil Dyed Check

At first glance, it appears to be a woven texture, with an interplay of lattice patterns. It carries a gentle and mysterious impression, as if wavering between the qualities of weaving and dyeing. The aim is to create a kimono that embodies the best of both worlds—the depth of weaving and the beauty of dyeing, harmoniously combined.

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

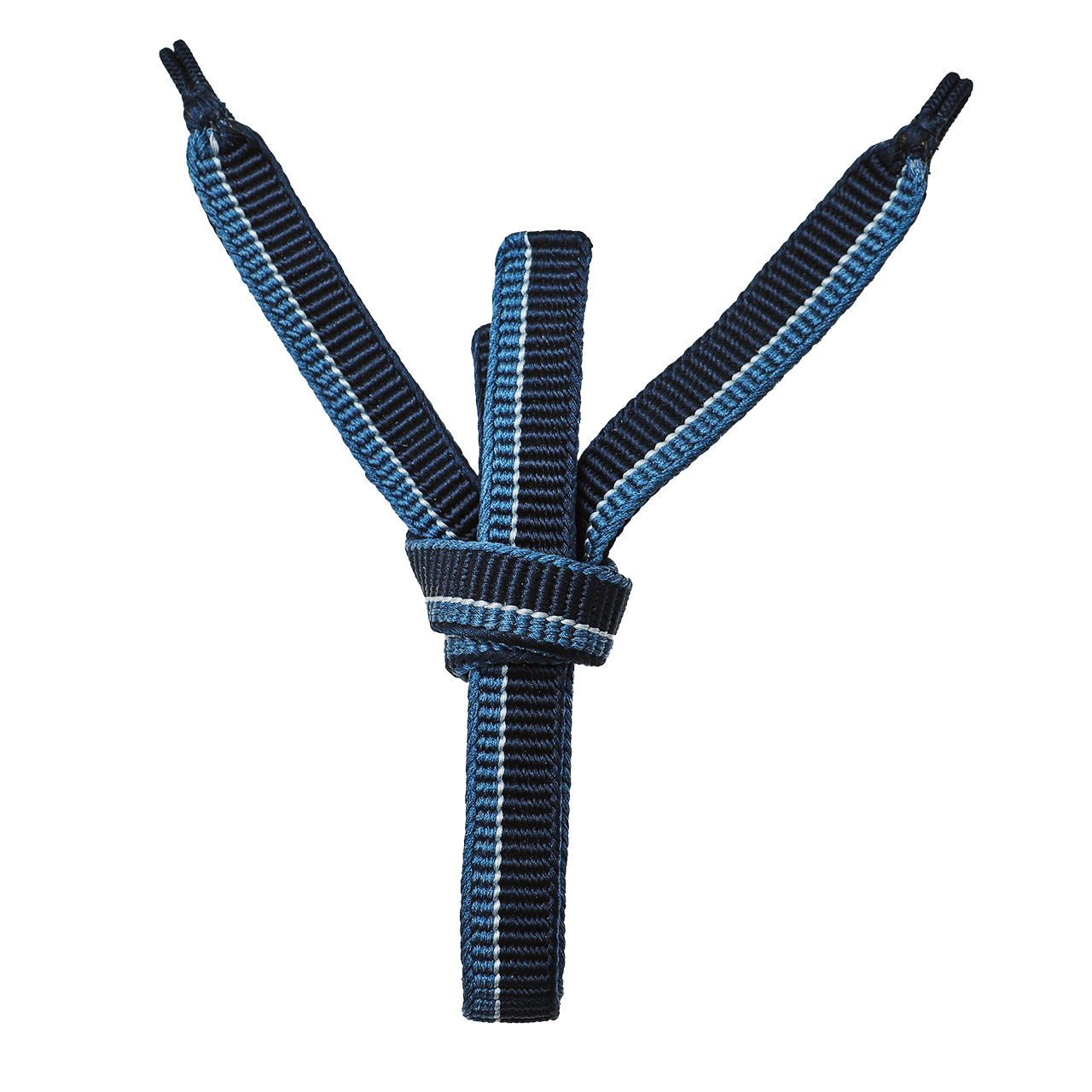

小物

小物

履物

履物

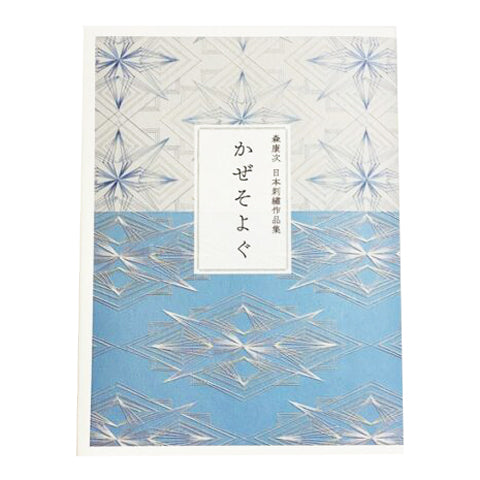

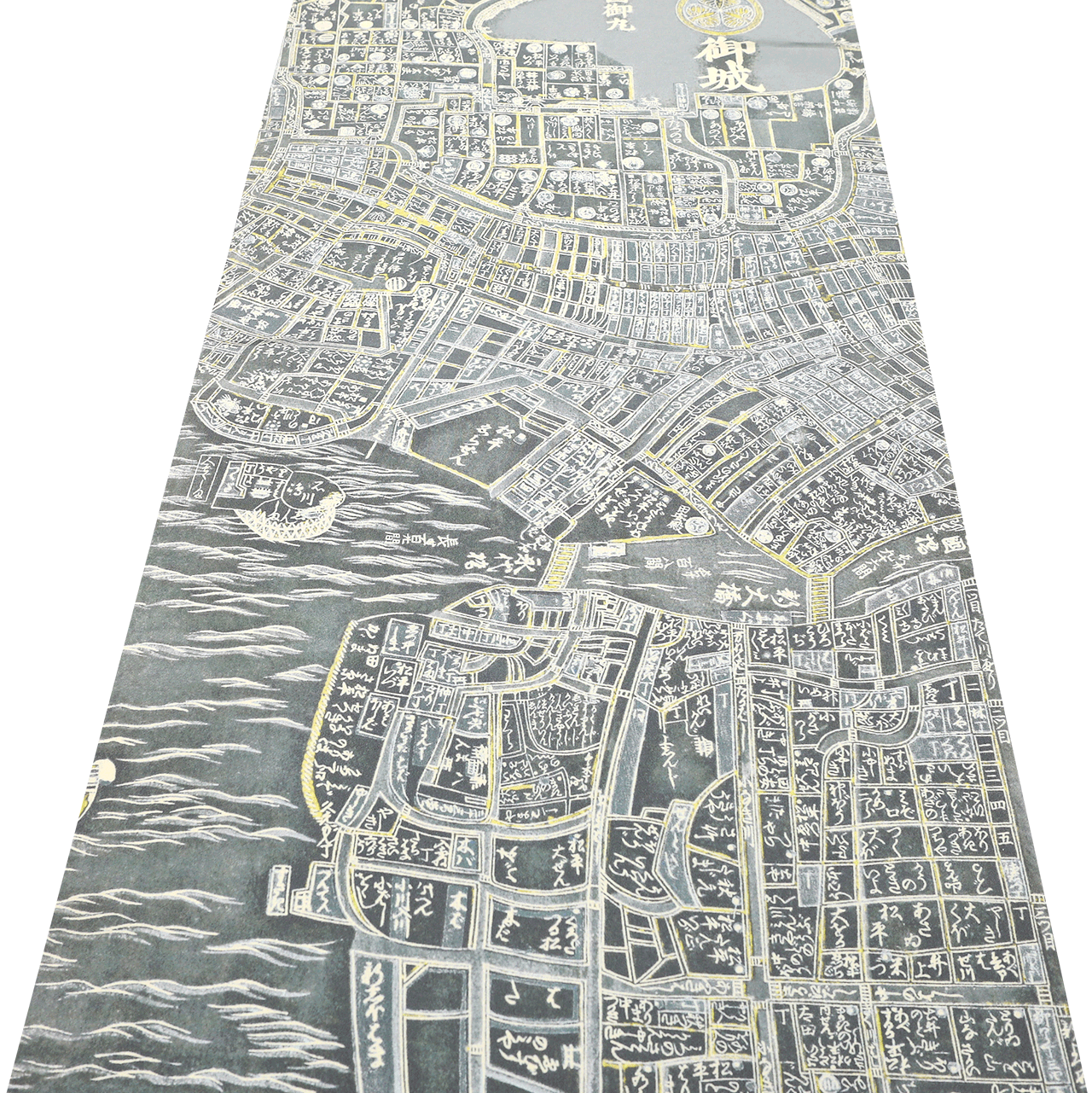

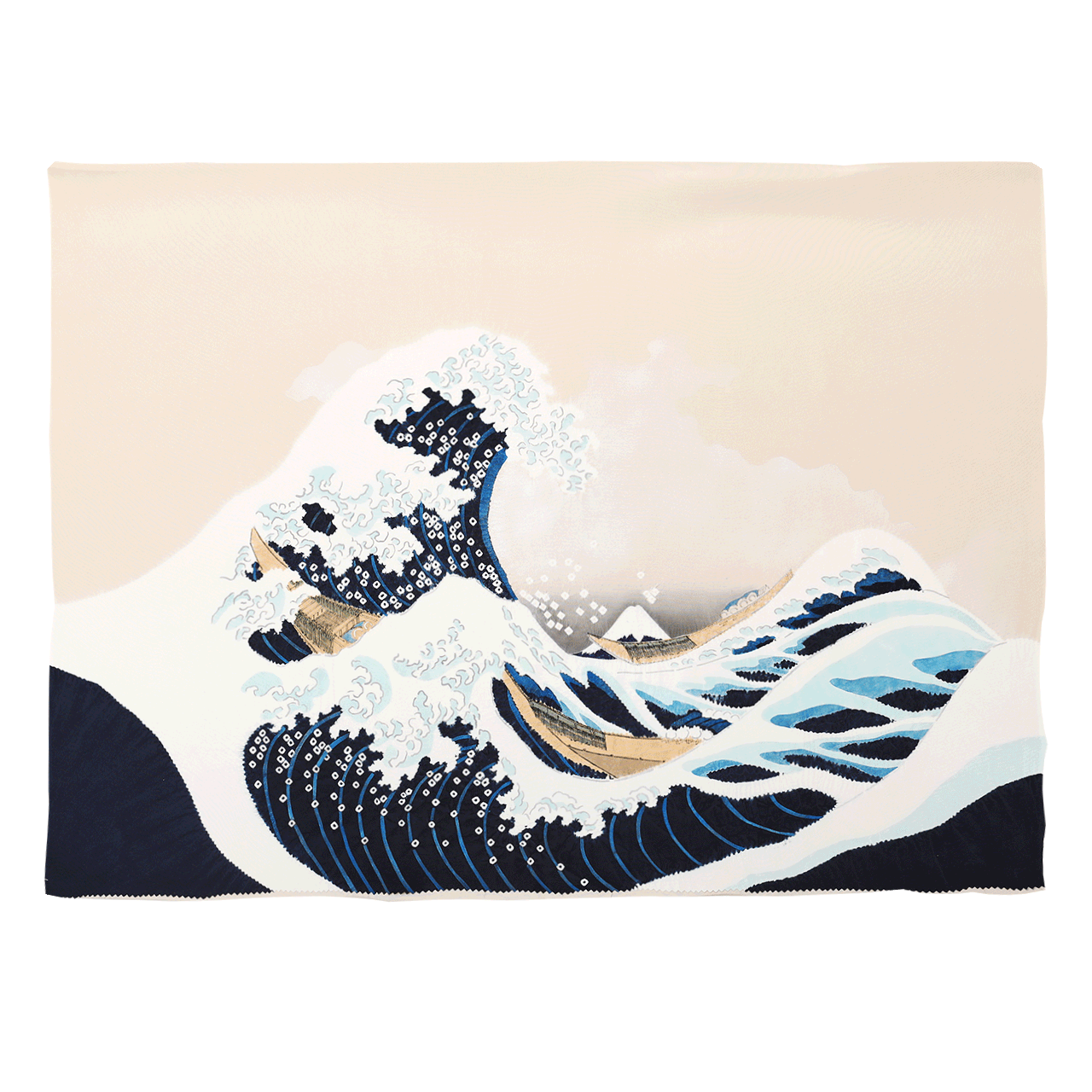

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

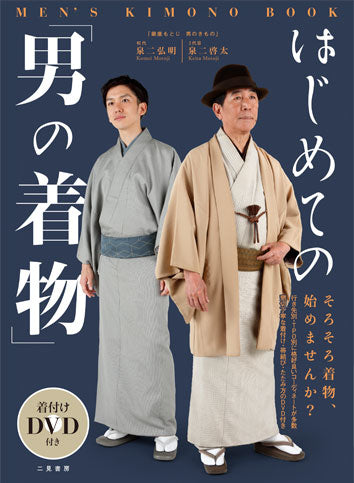

書籍

書籍