Writing by craft writer TODATE, Kazuko - Translated by Ginza Motoji in 2025

Indigo, Japan Blue.

During the Meiji era, the British chemist R.W. Atkinson (1850–1929), who visited Japan, famously described his impression of the country as Japan Blue—a reference to none other than ai, the deep blue of traditional Japanese indigo dye. By the late Edo period, indigo had already become an integral part of daily life, shaping Japan’s visual landscape. Ukiyo-e prints from that time depict elegant women dressed in indigo kasuri patterns and scenes of indigo-dyed fabrics fluttering in the wind. Even Eiichi Shibusawa (1840–1931), the renowned entrepreneur born in the late Edo period, came from a family that produced and sold ai dye cakes.

In 2024, the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art held an exhibition titled Kurume Kasuri and the Matsueda Family, showcasing the work of Matsueda Tamaki (1905–1989) and other artisans of the Matsueda family, who dedicated their lives to ai. Around the same time, the Kurume City Art Museum hosted The Story of Indigo, where Tamaki’s works were also featured.

Unlike dyers who focus solely on indigo-dyed textiles, the Matsueda family—Tamaki included—were weaving artists. They dyed cotton threads with ai before weaving them into intricate patterns on the loom. Their work employed the meticulous kasuri technique, in which threads are carefully tied and resist-dyed before weaving, creating structured designs within the very yarn itself. The distinctive vibrancy of the Matsueda family's Kurume kasuri stems from this unique process, where patterns emerge through the deliberate interplay of indigo and white in the woven fabric.

The Origins of Kurume Kasuri and the Matsueda Family

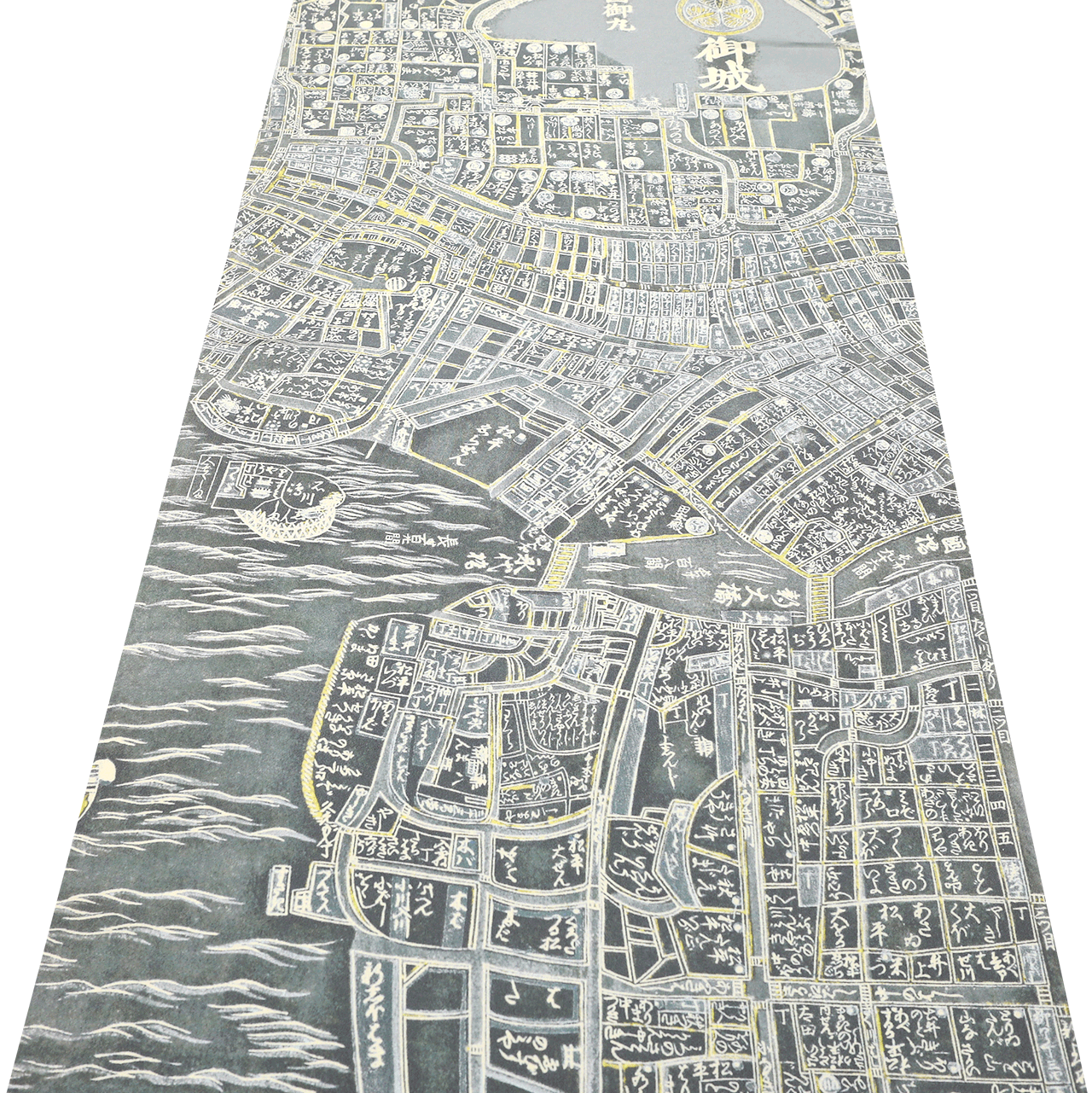

Kurume Kasuri, which has a history of about 200 years, first developed around 1800 in the Edo period as a local industry in Kurume and the Chikugo region of Fukuoka Prefecture. In Kurume City, Tokunji Temple is home to the grave, bust, and monument of Inoue Den (1788–1869), who, as a teenager, discovered the principles of the kasuri technique and passed her knowledge on to many others. By the late Edo period, around 1839, a more intricate form known as e-gasuri—pictorial kasuri, in which designs were drawn onto threads before weaving—had also emerged.

The Matsueda family's involvement in Kurume Kasuri began in the late 19th century with Matsueda Kōji (dates unknown–1900), who established a weaving business. His successors, the second-generation Ei (1875–1953) and third-generation Tamaki (1905–1989), refined and expanded the family’s craft. Meanwhile, Kōji’s second son, Kiyoji (1865–1943), played a key role as a dyestuff merchant, sourcing Awa-ai indigo from Tokushima.

The exceptional quality of Kurume Kasuri in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is evident in a pattern sample book that won a First-Class Silver Medal at the 1907 Tokyo Industrial Exposition (Figure 1). Additionally, fragments of kasuri fabric preserved by the Matsueda family from the 1910s–1920s showcase various adaptations of the igeta (well-frame) motif. Beyond kimono, e-gasuri pictorial pieces were also created, featuring large rectangular kasuri patterns for futon fabric. These textiles, adorned with auspicious motifs, were often made to celebrate marriage and other important life events.

(Figure 1)

The Kurume Kasuri of the Matsueda Family and the Artistic Identity of Matsueda Tamaki

Among those who pioneered the fusion of Kurume Kasuri as both a livelihood and a means of personal artistic expression was Matsueda Tamaki.

After World War II, Kurume Kasuri was designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property, with artisans officially recognized under the Kurume Kasuri Preservation Society. However, the intricate production process, which involves as many as 36 steps, naturally requires the cooperation of family members. Tamaki, too, was supported by his wife, Haji (1907–1990), and his eldest son Eiichi’s (1929–2016) wife, Kinue (1933–2021), both of whom were highly skilled weavers.

Among the many stages of Kurume Kasuri production, the three key requirements for its designation as an Important Intangible Cultural Property are:

- Hand-tying the kasuri threads,

- Dyeing with natural indigo,

- Hand weaving on a traditional loom.

However, for an artist working in Kurume Kasuri, these three aspects are merely the foundation. The process begins with sketching original designs, transforming them into e-gami (pattern blueprints) that objectively map out the intended woven motifs. Based on these blueprints, designs are drawn onto e-dai (pattern boards) to guide the kasuri thread markings, which then serve as a reference for determining where the threads should be tied and resist-dyed. This meticulous approach is essential, as weaving—especially pictorial kasuri—requires not only artistic intuition but also precise mathematical planning. The artist must translate their vision into a structured numerical relationship between warp and weft threads.

Tamaki held himself to a strict discipline of creating "one design per day." From the late 1950s onward, he presented his artistic vision and aesthetic sensibilities through exhibitions organized by the Japan Kōgei Association. His work spanned from bold, figurative motifs to intricate abstract patterns, often imbued with a sense of poetic lyricism and auspicious themes, which became hallmarks of his style.

In addition to deep indigo hues, Tamaki also introduced a lighter, intermediate shade of blue. This brighter water-blue tone was notably used in designs such as Ken-koku (献穀, 1976) (Note 3, Figure 2), which was chosen as the bridal attire for Matsueda Sayoko.

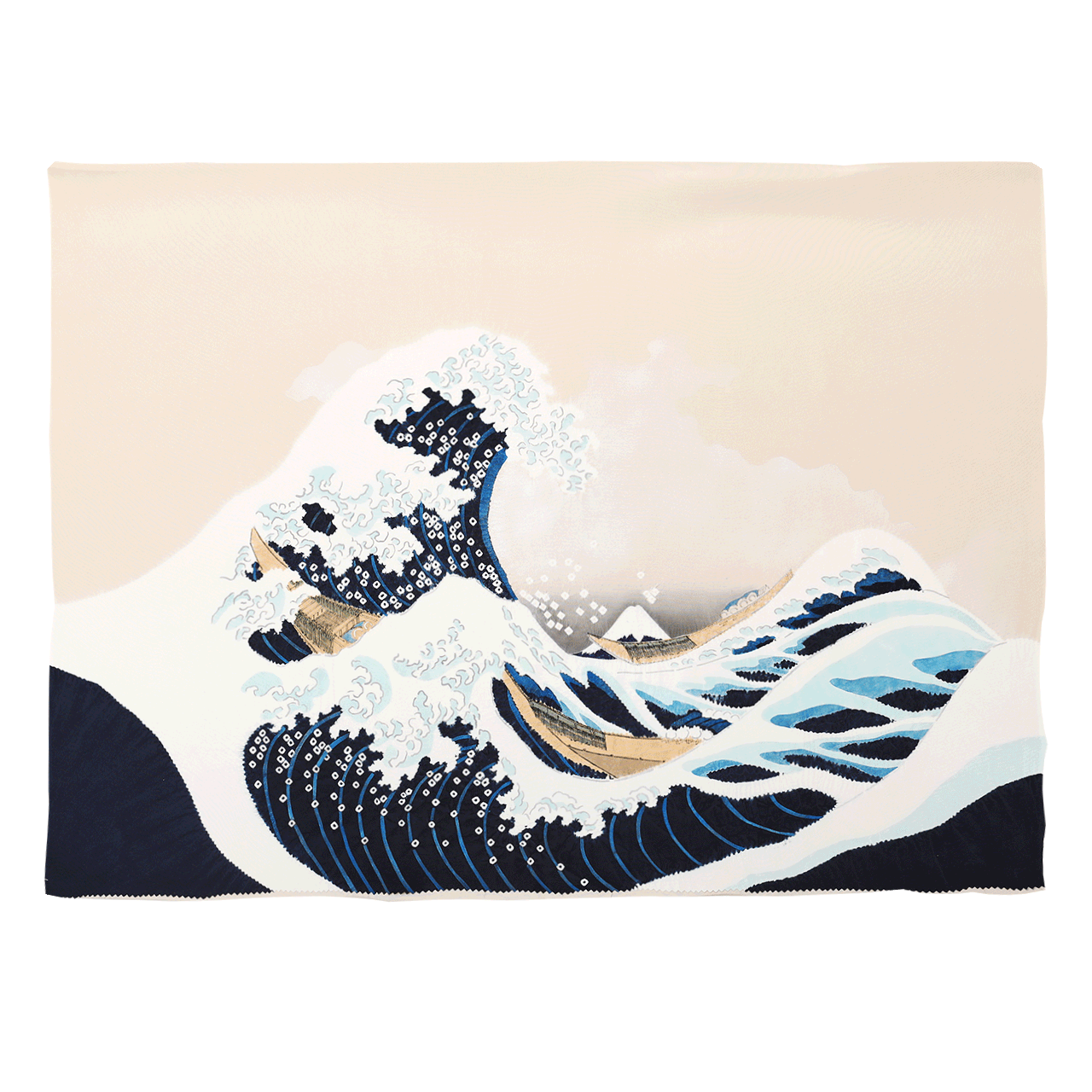

One of his most renowned works, Kaze to Hikari (風と光, 1972), captures the interplay of early summer light filtering through a grape trellis. By incorporating intersecting lines to suggest the vines and leaves, and using contrasting indigo and white kasuri patterns, he created a composition that radiates luminosity against the deep navy background. This suggests that Tamaki had already discovered the expressive potential of light within the indigo-and-white interplay of Kurume Kasuri.

Matsueda Tetsuya: Weaving the Brilliance and Traces of Formless Light into Kasuri Patterns

From his early teenage years, Matsueda Tetsuya (1955–2020) became familiar with the management of indigo vats and the dyeing process. He further developed Tamaki’s experiments and insights, expanding upon them in significant ways.

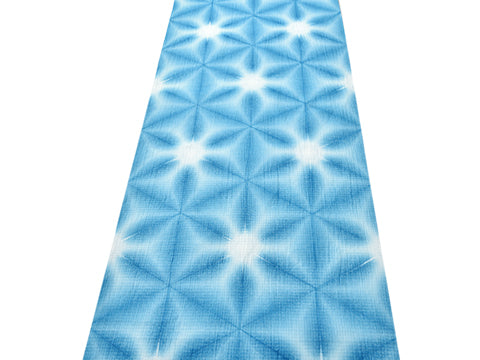

The first key aspect of his work was his deliberate focus on the expression of light. In an interview with the author, Matsueda spoke about his appreciation for the beauty of the night sky in Tanushimaru, where his workshop was located, as well as his fascination with fireworks. This interest in light and brilliance became evident in his works, particularly from around 2000 onward, as reflected in the titles of his submissions to the Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition. Additionally, his textiles featuring floral motifs, such as Hydrangea (2001) and Refreshing Breeze (2013), which depict wisteria blossoms, make skillful use of the white areas in the warp and weft kasuri technique to evoke a shimmering effect. Furthermore, Matsueda experimented with portraying the intangible and ever-changing trails of light, as seen in his Fireworks series (Fig. 3), and works such as Radiance (2020), now held in the collection of the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

The second major focus of his work was his exploration of the depth and luminosity of indigo, which plays a crucial role in enhancing the beauty of patterns. Matsueda conducted extensive research and refinements to improve both the vibrancy and durability of lighter indigo shades, such as chū-ai (medium indigo) and tan-ai (light indigo). By carefully monitoring the living state of the indigo vat, he developed techniques for layering thin applications of dye. Dyeing a fabric around 30 times enhances both its color intensity and fastness, while a deep navy hue requires more than 40 rounds of dyeing. If repeated about 70 times, the fabric takes on a nearly blackish-purple tone, with a subtle reddish hue unique to natural indigo.

Notably, the wood ash required for the natural fermentation of the indigo vat was supplied by Soeda Kazunobu, a ceramic artist from Fukuoka Prefecture and a member of the Japan Kōgei Association. Matsueda’s dedication to indigo expanded the depth and range of his family’s signature indigo hues, evolving them over time. Today, his eldest son, Matsueda Takahiro (b. 1995), continues this legacy as the primary inheritor of his father’s craft.

(Figure 3)MATSUEDA, Tetsuya - Kurume Kasuri Kimono "Dreams of Fireworks"

Matsueda Sayoko: The Dynamism of Composition Through Abstract Patterns

Matsueda Sayoko (b. 1956) studied at the Gujo Craft Research Institute under Munehiro Rikizo (1914–1989). In 1982, she began exhibiting her works, including at the 17th Seibu Craft Exhibition. Three years later, after marrying Tetsuya, she became one of the pioneering figures to establish the role of a female creator in the world of Kurume Kasuri. While Inoue Den paved the way for women as weavers, Sayoko, as both a skilled technician and an artist, developed her own unique designs and hand-drawn patterns, which she then brought to life through her weaving.

Kurume Kasuri is a labor-intensive craft, and at a time wheyn it was commonly believed that only one person per household could take on the role of creator (An independant artist working under their own name), Sayoko’s artistic endeavors were supported by her husband, Tetsuya, and the rest of the Matsueda family. Today, she serves as vice-chair of the Association of Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume Kasuri Techniques and is actively engaged in training the next generation of artisans.

Sayoko’s body of work is expansive, but it is particularly characterized by the rhythm and dynamism of abstract geometric patterns. She skillfully utilizes the shape of the kimono to amplify these elements, creating bold and powerful compositions.

Sayoko has also stated, “For me, too, light is a central theme.” However, whereas Tetsuya’s imagery often evoked the light of the night sky, Sayoko tends to capture the shimmering specks of daylight filtering through swaying leaves. This approach lends her work a sense of openness, as if a breeze were flowing through the entire kimono, evoking the natural rhythms of the world. Her piece Warm Breeze (2000) is a notable example of this expression.

Matsueda Takahiro: A Spirit of Inquiry and Diverse Challenges

Matsueda Takahiro grew up closely observing the work of his parents. Even as his father, Tetsuya, fell ill, Takahiro continued to seek his guidance until the very end. In 2021, he made his first successful entry into the 55th Seibu Traditional Craft Exhibition, marking an early milestone in his career.

His debut work, Green Willow, featured a combination of indigo shades that created wide, striped color fields across the entire kimono. Interspersed throughout were delicate kasuri motifs reminiscent of the swaying leaves of a willow tree, lending the piece a distinctive softness. His exploration of color compositions that incorporate areas of white space is also evident in works such as Sound of the River (2024).

Meanwhile, Light in the Forest: The Sound of Rain (2021), which won the Japan Kōgei Association Encouragement Award at the 68th Japan Traditional Craft Exhibition, presents a meticulously arranged abstract pattern that establishes a flowing vertical rhythm. It evokes the shimmer of trees illuminated by raindrops and the sensation of hearing the gentle sound of rain. Following in this lineage, Luminous Haze (2024) centers on a cross-like motif, conveying an embracing sense of “light” while balancing three points of illumination within a subtle vertical rhythm. His work also includes more dynamic compositions, such as Flight (2023) (Fig. 4), which transforms the image of soaring birds into an expressive pattern. With each exhibition, Takahiro presents a distinct artistic approach, demonstrating his versatility.

Takahiro has stated that his creative theme is “a different expression of light than my father’s.” However, alongside his exploration of light, his works also reflect a deeper inquiry into kasuri itself—what defines its blurred effect, what possibilities exist in e-gasuri (pictorial kasuri), and how to effectively combine indigo with other plant-based dyes to create meaningful designs. Each of his pieces reveals his relentless pursuit of new challenges and his inquisitive spirit.

Currently, Takahiro is undergoing rigorous training as an apprentice in preparation to become a member of the Association of Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume Kasuri Techniques. As both an artist of the Matsueda family and a craftsman shaping the future of his region, he is certain to play a vital role in carrying Kurume Kasuri forward as a cultural tradition, working alongside the young artisans learning within the Matsueda household.

(図4)松枝崇弘作 久留米絣着物「飛翔」

The Kurume Kasuri of the Matsueda Family: Indigo and Light as the Foundation of Expression

The world of Kurume Kasuri as expressed by the Matsueda family encompasses a broad spectrum, ranging from figurative motifs that depict concrete subjects to intricate abstract patterns formed by continuous repetition. Upon closer inspection, however, all of their designs share a natural softness and a subtle, pleasant wavering effect. This is likely due to the way the contours of the patterns are expressed through kasuri-dyed threads.

In their creative process, Matsueda Tetsuya actively pursued light as a central theme. However, even in the work of Tamaki, an awareness of light can already be observed, and both Sayoko and Takahiro have each explored the theme of light in their own distinct ways. It is likely that people in the past also saw reflections of the starry night sky in the arare (hail) patterns of Kurume Kasuri. The Monument to Kurume Kasuri, erected in 1885 within the precincts of Suitengu Shrine in Kurume, even bears the inscription "Snow and Hail Filling the Sky." If one of the defining characteristics of Kurume Kasuri is the brilliance of its white motifs set against deep indigo backgrounds, then this association with celestial light seems only natural.

In particular, the Matsueda family's dedication to dyeing threads with natural indigo has played a significant role in enhancing the depth and expansiveness of their kasuri patterns. The range and richness of indigo shades they have cultivated—something that might be called Matsueda Blue rather than Japan Blue—is inseparably tied to the beauty of their kasuri designs. This interplay of indigo and light not only enhances the elegance of the wearer but also brings a radiant energy to those around them.

Profile: Todate Kazuko

Born in Tokyo. After working as a museum curator, she is currently a professor at Tama Art University and a visiting professor at Aichi University of the Arts. She is also a craft critic and craft historian.

Todate has curated exhibitions, written catalog essays, and given lectures at museums and universities both in Japan and abroad, including Tate St Ives in the UK, the traveling exhibition Forms of Handwork, Smith College Museum of Art in the US, and Frankfurt Museum of Applied Arts in Germany.

She has also served as a juror for numerous competitions, including the Cheongju International Craft Biennale (Korea), Kanazawa World Craft Triennale, Nitten, and the Japan Traditional Craft Exhibition.

Her publications include Katsuma Nakamura and the Lineage of Tokyo Yūzen (Senshoku to Seikatsu-sha) and Fired Earth, Woven Bamboo: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics and Bamboo Art (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA). She is currently writing the "KOGEI!" column, published in the Mainichi Shimbun every second Monday of odd-numbered months.

Chronology: Matsueda Sayoko

- 1956 Born in Kumamoto City

- 1979 Studied under Munehiro Rikizo

- 1982 First accepted into the Seibu Craft Exhibition (Japan Kōgei Association)

- 1984 Awarded the Encouragement Prize at the Fukuoka Prefectural Exhibition

- 1985 Married Matsueda Tetsuya

- 1988 First accepted into the Japan Traditional Craft Exhibition

- 1989 Awarded the Asahi Shimbun Gold Prize at the Seibu Craft Exhibition

- 1990 Won the Grand Prize and Minister of International Trade and Industry Award at the 15th All-Japan Newcomer Dyeing & Weaving Exhibition

- 1994 Certified as a member of the Association of Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume Kasuri Techniques

- 1997 Recognized as a full member of the Japan Kōgei Association

- 2012 Awarded the Nihon Keizai Shimbun Prize at the 46th Japan Traditional Textile Exhibition

- 2015 Won the Encouragement Prize and Sanyo Shimbun Prize at the 49th Japan Traditional Textile Exhibition

-

2019 Awarded the Fukuoka City Mayor’s Prize at the 54th Seibu Traditional Craft Exhibition

- Received the Mitsukoshi Isetan Prize at the 53rd Japan Traditional Textile Exhibition

- 2021 Awarded the Asahi Shimbun Grand Prize at the 55th Seibu Traditional Craft Exhibition

- 2022 Received the Nihon Keizai Shimbun Prize at the 56th Japan Traditional Textile Exhibition

- 2023 Received the Fukuoka Prefecture Education and Culture Award

Currently serves as Vice Chair of the Association of Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume Kasuri Techniques, a full member of the Japan Kōgei Association, and a member of the Fukuoka Prefectural Art Association.

Chronology: Matsueda Takahiro

- 1995 Born in Kurume City, Fukuoka Prefecture

- 2017 Graduated from Saga University, Faculty of Economics, and joined Nippon Express Co., Ltd.

- 2020 Resigned from the company to fully dedicate himself to the family craft

-

2021

- First accepted into the 55th Seibu Traditional Craft Exhibition

- First accepted into the 68th Japan Traditional Craft Exhibition, receiving the Japan Kōgei Association Encouragement Prize

- 2022 First accepted into the 56th Japan Traditional Textile Exhibition

-

2023

- Recognized as a full member of the Japan Kōgei Association

- Awarded the Encouragement Prize at the 57th Seibu Traditional Craft Exhibition

- Received the Fukuoka Governor’s Prize at the Fukuoka Prefecture Traditional Craft Exhibition

Currently a full member of the Japan Kōgei Association and an apprentice in the Association of Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Property Kurume Kasuri Techniques.

松枝家の久留米絣―藍と光の探求と展開|3月催事

The Matsueda family has a history spanning over 150 years since its founding in the early years of modern Japan (around the late 19th century). Last year, in honor of the 120th anniversary of Matsueda Tamaki’s birth, the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art held a special exhibition, Kurume Kasuri and the Matsueda Family, which captivated visitors from Japan and beyond.

Now, at Ginza Motoji, we are presenting a rare exhibition featuring works from four generations of the Matsueda family—Matsueda Tamaki, Matsueda Tetsuya, Matsueda Sayoko, and Matsueda Takahiro—including pieces from the museum’s collection. This is a unique opportunity to appreciate their mastery of egasuri (pictorial kasuri patterns), the rich tonal variations of deep and pale indigo, and the distinct artistic expressions of each generation.

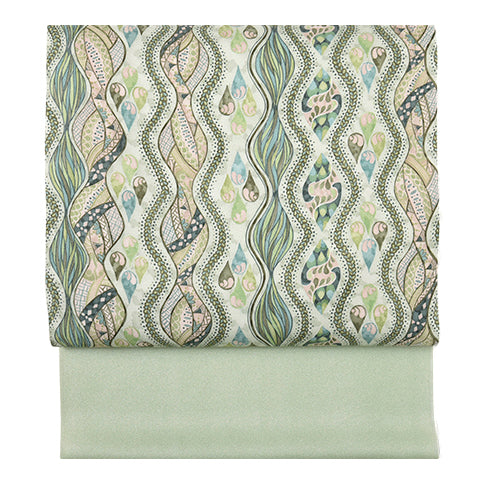

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

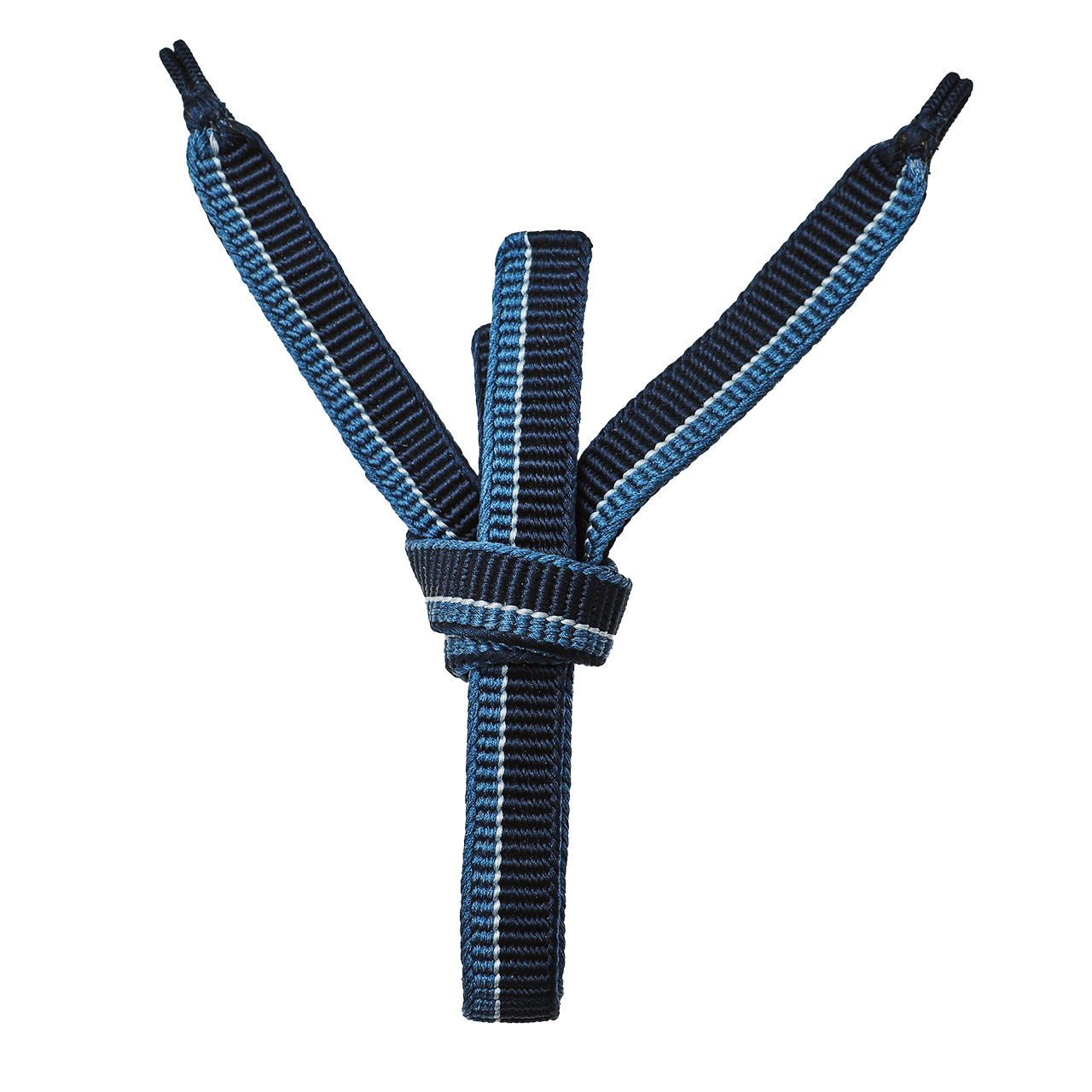

小物

小物

履物

履物

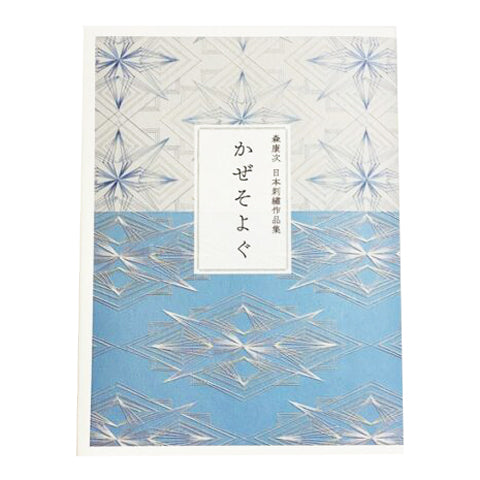

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍