The Making of Yuki-Chijimi

The Yuki Chijimi Revival Project was launched in 2021 to rekindle interest in the Chijimi weave and reproduce two historical Yuki Chijimi patterns. The project used Platinum Boy silk, a unique silk exclusively available at Ginza Motoji. The revived patterns were selected through a customer popularity vote at Ginza Motoji, based on antique Chijimi fabric fragments. This text is being translated from Japanese to English in 2025.

The Production Process of Yuki Chijimi

1. Making the Thread

2. Choosing the Colour

3. Kukuri and Thread Twisting

4. Dying

5. Weaving

6. Finishing

This is a 6 part series. Links to the other 5 chapters will be linked at the bottom of the article as they are posted.

Step 1:Thread Pulling (Ito-Tsumugi, 糸つむぎ)

◆Pulling thread from Platinum Boy silk floss.

The first step in making Yuki Chijimi is to create the silk threads. These threads are not made by machine but spun entirely by hand. In Yuki, the process of spinning threads from silk floss is often referred to as "ito-tori." Both Yuki Tsumugi and Yuki Chijimi depend heavily on the quality of the threads, as this directly influences the final fabric's quality.

For Yuki Chijimi, in particular, the process includes "twisting," where the threads are twisted to achieve their characteristic spongy texture. Uneven threads with variations in thickness can break easily, so producing smoother, more uniform threads is essential.

Producing one tan (enough fabric for a single kimono) of Yuki Chijimi requires an astonishing length of thread—enough to circle the entire Yamanote Line (approximately 53 kilometers)! Intricate kasuri patterns demand even finer and longer threads. Each of these threads is meticulously spun by hand.

The above picture shows the silk floss made from the spring cocoons of 2021. These cocoons, carefully raised by our contracted sericulture farmers, were boiled and hand-stretched into a bag-like shape. Skilled silk artisans from Hobara, Fukushima—renowned for their expertise in silk floss production—transformed them into soft and lustrous, high-quality silk floss. These bundles were then delivered to master thread makers through Yuki Tsumugi producer Okujun.

the silk floss () is hooked onto a stand called a tsukushi, and cocoon threads are gradually pulled forward by hand to make the thread. These threads are then collected in a specialized container called oboke. The rhythmic kyu kyu sound of the silk fibers being pulled is a sign of a skilled artisan at work.

Platinum Boy thread is so strong that the thread makers say at the end of a long day of spinning thread, there fingers feel like there going to fall off.

The oboke pail filled with freshly drawn platinum boy thread. I oboke of threads is called 1 pocchi. It takes about 5-10 days to produce this much thread. It is an extremely painstaking job.

Step 2:Choosing the Pattern and Colour

The mission is "revival", to faithfully recreate the kasuri patterns woven by artisans of old, we carefully examine fragments just a few centimeters square under a magnifying glass. By analyzing the relationship between the warp and weft threads, we determine how many kasuri threads need to be woven into the warp and weft. This process is then meticulously transcribed onto graph paper as a detailed blueprint.

The word chijimi in Japanese can mean "to shrink." Yuki Chijimi is a type of silk fabric where the threads are twisted before weaving. Once woven, the fabric shrinks slightly, creating its characteristic bumpy texture. This shrinkage must be carefully considered when designing patterns, as the drafts need to account for the anticipated shrinkage, requiring precise adjustments. This intricate work relies on years of experience, as well as the passion and dedication of artisans who spare no effort in perfecting their craft.

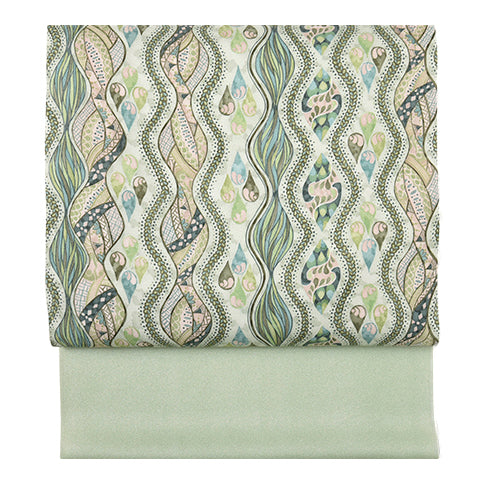

This pattern is called "Ken-Hanabishi". The draft behind is pre revision, and the one in the forground is the final version. It is refined, and executed with sharper lines as opposed to the round petals of the previous pattern.

Yagasuri, is a traditional pattern, depicting the feathers on an arrow. The pattern on the original draft was wider, but was slimmed down and sharpened for a more contemporary feel.

◆Choosing the Color

After the patterns are decided, the colors are selected using dyed thread samples. It is important to consider that the interplay between the warp and weft threads will alter the way the colors appear in the finished fabric, making them look different from the dyed silk threads on their reels.

The dyes used for thread dyeing come in many varieties, and just as the tone of a color varies with watercolors, acrylics, or oil paints in painting, the type of dye affects the color’s appearance on threads. To achieve the desired outcome for this project, we carefully discuss and select the most suitable dye.

Test-dyed thread bundles are compared to antique fabric fragments, assessing depth, saturation, and luster. The final color is chosen through meticulous evaluation of subtle differences, with experts analyzing how the colors appear under various lighting conditions, including artificial and natural light.

Threads dyed with different dyes or concentrations may appear to be the same color at first glance, but under light, subtle differences in hue become noticeable.

A meeting between Koumei and Keita Motoji with Okujun Director Okuzawa Yoriyuki (left).

Find out more in Part 2.

Platinum Boy for Modern Wear: The "Yūki-Chijimi Revival Project"

When Keita Motoji, the second-generation head of Motoji, came across a sample book from the Yuki Tsumugi producer Okujun, he was deeply moved by the bold and free-spirited kasuri patterns of Yūki-Chijimi from the past. These small fragments of fabric were brimming with the artisans’ spirit and vibrant energy.

"By reviving these patterns, we can learn from the wisdom of our predecessors."

With this mission in mind, master artisans pour their expertise and passion into creating the ultimate lightweight kimono, Platinum Boy Yūki-Chijimi. Over the course of a year, this masterpiece is painstakingly brought to life, offering unparalleled comfort and craftsmanship.

Why Revive Yūki-Chijimi, Why Now?

Yūki-Chijimi Was Once More Popular Than Yūki-Tsumugi

Known as the "King of Tsumugi," Yūki-Tsumugi is a luxurious textile woven with hand-spun, almost untwisted mawata silk threads, making it incredibly light and warm. Its unmatched comfort has earned it admiration from countless kimono enthusiasts. In 1956, it was designated as Japan's second Important Intangible Cultural Property after Echigo-jōfu.

In contrast to Yūki-Tsumugi's rising prominence, another equally captivating textile—Yūki-Chijimi—faces a critical moment in its legacy.

Derived from the word chijimu (to shrink), chijimi refers to textiles that undergo a shrinking process, creating a crinkled texture known as shibo. Unlike Yūki-Tsumugi, its production involves twisting the hand-spun threads. The tension from the twisting naturally creates a crisp surface texture, resulting in a breezy fabric ideal for warmer seasons.

Although Yūki-Tsumugi boasts a 2,000-year history, Yūki-Chijimi emerged in the Meiji era (circa 1902). Its unique blend of crisp texture and bold kasuri designs became immensely popular, to the point where, by the early Shōwa era, Yūki-Chijimi accounted for about 80% of production in the Yūki-Tsumugi region.

However, as Yūki-Chijimi’s popularity grew, production of Yūki-Tsumugi declined. To preserve Yūki-Tsumugi, it was designated a cultural property in 1956, reversing market demand. Yūki-Chijimi production plummeted and today accounts for less than 10% of total production, making it a rare textile on the brink of obscurity.

"Platinum Boy × Yuki-Chijimi"

Revival of Two Rare Textiles

This project brings together Motoji's exclusive domestically produced silk, Platinum Boy, and the once-beloved Yūki-Chijimi. Using sample designs from the golden era of Yūki-Chijimi, two patterns—one for men and one for women—have been selected through a public vote for this revival.

During the Meiji era, Japan was the world’s leading silk exporter. Yet today, domestic silk production accounts for less than 1% of the market, overtaken by imports.

Platinum Boy is a revolutionary silkworm species developed by Dr. Akio Ōnuma over 37 years. Its silk’s radiant whiteness earned it the name "Platinum."

Now, with this innovative silk that didn’t exist during Yūki-Chijimi’s heyday, Motoji collaborates with modern connoisseurs of style to weave new life into timeless patterns. This revival project blends tradition and innovation, and we’ll be sharing updates throughout the journey to completion.

Stay tuned for this exciting revival of a dream textile.

The Winning Men's Pattern

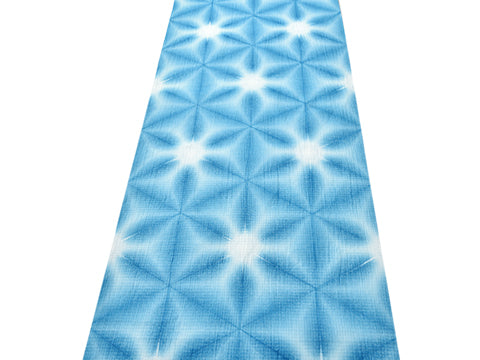

Yagasuri, Tate Moro Kasuri (矢絣、経モロ絣 )

The loom used in weaving Yuki, known as a jibata, is unique compared to other looms because only the bottom threads move up and down. As weaving progresses, the top and bottom threads tend to shift out of alignment, so it is common practice in the region to include kasuri (ikat patterns) only in the top warp threads. This scrap of fabric features a design called "Moro-gasuri," where kasuri patterns are incorporated into both the top and bottom threads—a method of creating kasuri that is now rarely seen.

The Winning Women's Pattern

Kenhanabishi, Yoko Kasuri (剣花菱,緯絣)

To weave Yūki-chijimi, hand-spun threads are alternately twisted with right and left twists and woven into the weft in an alternating pattern. On the other hand, threads with patterns, known as kasuri threads, are left untwisted. In weft kasuri like this fabric scrap, the weaving follows a sequence of right-twisted threads, kasuri threads, left-twisted threads, and kasuri threads. This method, which involves a high density of kasuri and significant weaving effort, is now rarely practiced.

MOTOJI, Keita speaks on Yuki Chijimi, (Japanese only)

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

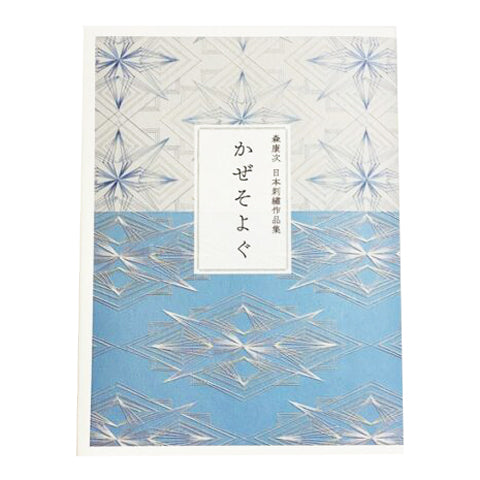

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍