The Origins of Oshima Tsumugi

Oshima Tsumugi is a renowned Japanese textile from Amami Oshima in Kagoshima Prefecture, admired for its intricate patterns, smooth texture, and natural sheen. Made from high-quality silk, it undergoes a unique mud-dyeing process using iron-rich soil and plant-based dyes to achieve its distinctive earthy tones.

According to legend, the origins of Oshima Tsumugi trace back to the era of the gods. Inspired by the revered figure Amamiko, who covered her head with rare silk, the island's women sought to emulate her by weaving textiles from precious silk materials called "chinken" and "chinkubi."

During the Taisho era (1912-1926), Oshima Tsumugi was woven using hand-spun yarn and featured a decorative float weave known as "hana-ori." This style, also referred to as "Hire," was popular on Amami Oshima and neighboring islands like Tokunoshima and Yoron Island. While hana-ori is no longer common, surviving examples are treasured as cultural artifacts.

Today, Oshima Tsumugi remains a symbol of refined craftsmanship and is cherished for its elegance and durability in formal wear.

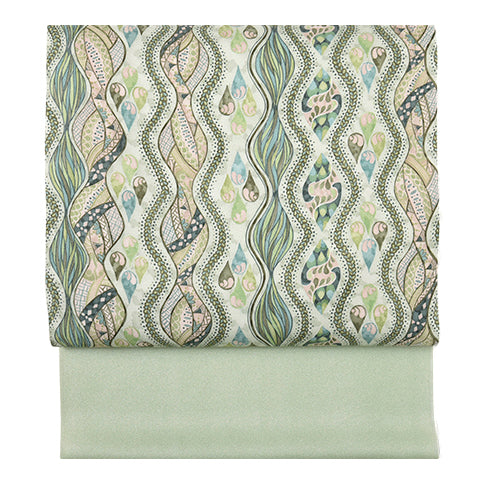

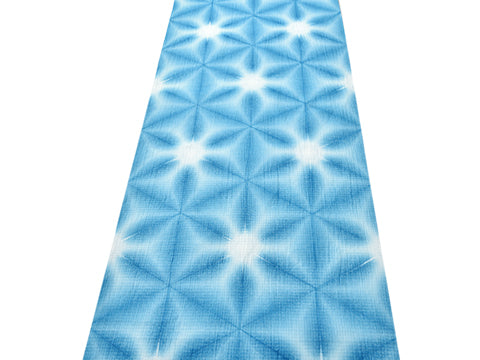

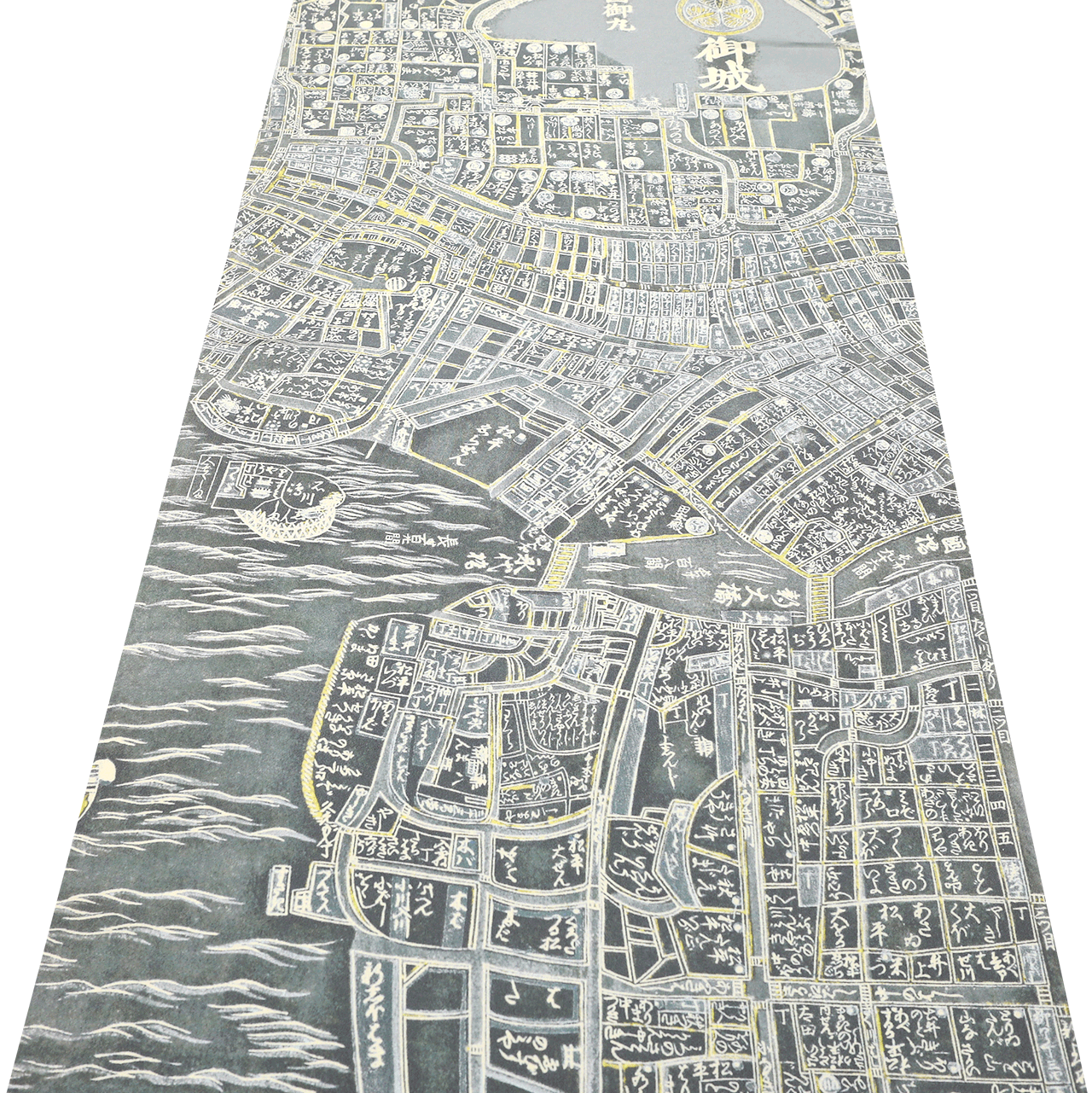

Above - Oshima Tsumugi Kasuri Patterns from the Taisho Era

Oshima Tsumugi of Edo Period

Above - Oshima Tsumugi Kasuri Patterns from the Taisho Era

The History of Oshima Tsumugi and Amami Oshima

Amami Oshima, with its subtropical climate, has long been rich in natural resources like sugarcane and yakogai (pearl oyster shells). Yakogai in particular was highly valued for its beauty and traded at high prices. The people of Amami Oshima engaged in trade with the mainland, exchanging their local products for various goods, leading to a prosperous lifestyle. On the northern side of the island, high-quality ito basho (banana fiber) was abundant, and most everyday clothing was made from this material.

Governance and Control

The Ryukyu Kingdom later established direct rule over Amami Oshima, sending officials to govern and turning the island into a territory under its control. During the Edo period, the precursor to modern Oshima Tsumugi began to emerge. In the early Edo era, hand-spun silk threads from raw silk (mawata) were dyed with plant-based dyes and woven on jibata (back strap looms). At that time, patterns were simple, consisting mostly of solid colors or stripes, as the intricate kasuri (ikat) patterns had not yet been developed.

In 1609, the Satsuma Domain invaded both the Ryukyu Kingdom and Amami Oshima, bringing the islands under its rule. Due to its abundance of resources, Amami Oshima was separated from the Ryukyu Kingdom and directly governed as a Satsuma territory. The exceptionally high quality of the tsumugi produced on the island caught the attention of the authorities, and it was reported to the Edo Shogunate alongside Ryukyu Tsumugi as a tribute. As a result, the tsumugi from Amami Oshima was categorized as “Ryukyu Tsumugi” at the time, leaving no distinct historical records of its own.

This shift marked the beginning of a harsh period for the island's residents, as they faced heavy taxation and oppression under Satsuma rule.

The Silk Prohibition Order

In 1720, a decree known as the “Silk Clothing Ban” was issued against the islands of Amami:

"From the rank of island officials down to common villagers, the wearing of silk garments is strictly prohibited."

This decree indicates that islanders were already producing and wearing silk Oshima Tsumugi by that time.

Cultural Recognition and Mud-Dyed Tsumugi

Evidence of the fame of Oshima Tsumugi during the Edo period can also be found in literary works. In 1688, the renowned writer Ihara Saikaku published "Koshoku Seisuiki" (The Life of an Amorous Man), in which he describes the attire of a pleasure-seeking customer as:

"Clad in black habutae silk with three crests, and a long haori of Oshima Tsumugi."

This suggests that even in the Edo era, the distinctive mud-dyed Oshima Tsumugi was highly prized.

Adapting Under Oppression

Despite the silk ban, the islanders adapted by using plant fibers such as karamushi (ramie), basho (banana fiber), and cotton for daily wear. Natural dyes were derived from local sources like shii (oak), yamamomo (bayberry), haze (wax trees), and other native plants, as well as the island’s signature mud-dyeing technique.

Even under strict regulations, the people of Amami Oshima devoted themselves to preserving their traditional weaving techniques. Using hand-spun yarn and simple looms, they maintained the craftsmanship of Oshima Tsumugi. During this period, patterns remained simple, consisting mainly of kasuri, stripes, and checks. Unlike the elaborate pictorial designs often seen in Ryukyu textiles, Amami Oshima’s kasuri patterns were characterized by their delicate, small-dot motifs, a style that continues to define Oshima Tsumugi today.

Oshima Tsumugi in the Meiji Era: The Birth of the Revolutionary Takabata Loom

In 1873 (Meiji 6), Amami Oshima was finally freed from the control of the Satsuma Domain, marking the beginning of full-scale production of Oshima Tsumugi.

After the end of the Satsuma Rebellion in September 1877 (Meiji 10), Oshima Tsumugi began to be distributed to markets not only in Kagoshima Prefecture but also in cities like Osaka. This marked the first time that the islanders could engage in commercial trade of their products.

Then, in 1883 (Meiji 16), a groundbreaking innovation brought significant changes to the weaving of Oshima Tsumugi, ushering in a new era for its production.

In 1883 (Meiji 16), a major innovation transformed the production of Oshima Tsumugi. Nagae Ieo from Akagina, Kasari Village (born in 1844), introduced a more efficient weaving loom called the choubata — the predecessor of the modern takabata loom.

The traditional jibata loom required weavers to sit on the floor and exert significant physical effort, making the process exhausting. Additionally, the delicate balance needed to control the loom often led to broken threads or uneven weaving. These challenges made it difficult to train new weavers, resulting in low production and an inability to meet growing demand.

To address these issues, Nagae established a workshop in Naze equipped with multiple takabata looms. He hired skilled artisans, laying the foundation for a more structured and efficient production system. Interestingly, his grandson, Nagae Akio, would later become a prominent figure in the production of Men Satsuma textiles. The name Men-Satsuma was coined by the author Mushakoji Saneatsu.

Innovation in Patterns and Designs

At the same time, advancements in pattern-making emerged. Moving away from the simple geometric designs of stripes and checks, a technique for creating curved floral and bird motifs was developed. Tozan Ijiro (d.1924 ) devised this groundbreaking method. He carefully arranged silk threads coated with adhesive on top of a painted floral design, applied ink marks, and then used a hand-tie-dye process to create the kasuri patterns. Through this technique, intricate and artistic designs were woven into the fabric.

This era saw the rise of famous patterns such as the "Yōjitsu-gara" from Akagina, Kasari Village and the iconic Tatsugo-gara from Tatsugo Village, which became widely produced and celebrated.

Expansion to National Markets and Increased Recognition

By around 1883 , Oshima Tsumugi began to be traded extensively in major markets like Kagoshima and Osaka, gaining recognition for its exceptional quality. The traditional dyeing method using the extract of the techigi tree and mud dyeing techniques elevated its reputation, spreading its fame across Japan.

Due to the increasing demand, hand-spun yarn was no longer sufficient for production, leading to the gradual introduction of tama-ito (silk filament yarn) as a substitute for hand-spun threads.

Formation of the Oshima Tsumugi Trade Association

During this period, the rapid growth of the Oshima Tsumugi market also brought challenges. The rise in demand led to the circulation of inferior products, threatening the textile's reputation. Concerned about this issue, Matsumoto Yaichiro, a merchant who had been working to expand the market and improve product quality in Osaka, took the initiative to establish the Oshima Tsumugi Trade Association in Naze.

To secure support for the association, Matsumoto returned to Amami Oshima and explained the history and current state of the industry to Fukuyama, the island's governor. With Fukuyama's endorsement, he was appointed as the association’s first director. The association brought together textile producers, implemented rigorous quality control measures, and promoted product improvement.

Initially, the stringent quality standards discouraged many weavers from joining the association. However, through the dedicated efforts of Fukuyama and Matsumoto, membership gradually grew. As a result, the association successfully upheld the quality of Oshima Tsumugi, ensuring its continued reputation as one of Japan’s finest textiles.

The introduction of Shimebata

Although the traditional jibata loom had been improved into the more efficient takabata loom, the crucial process of kasuri binding (to create the patterns on the thread) remained dependent on traditional hand-tying methods. This manual process limited productivity and posed challenges in achieving intricate kasuri patterns.

Around 1901, a pioneer named Shigei Kobou began researching the use of a binding method called orijime to create kasuri thread. However, he passed away in 1907 (Meiji 40) at the age of 36, before his research could be put into practical use.

One of the individuals who frequently visited Shigei’s workshop was Nagae, previously mentioned for his contributions to loom development. In 1907 , Nagae succeeded in completing a new kasuri-binding technique known as Futsujime. By around 1909, he made this technique public.

This innovation led to the development of the shimebata binding loom used today. With the shimebata, weavers could produce highly detailed kasuri patterns with greater efficiency. As a result, the reputation of Oshima Tsumugi grew even further, establishing it as one of Japan’s most esteemed textiles.

Patterns of Meiji, Taisho,

During the Meiji era, the most common designs for Oshima Tsumugi were stripes, checks, and solid colors, primarily dyed using the traditional mud-dyeing technique. The patterns tended to be intricate and geometric, reflecting a preference for finer, more subdued motifs.

However, from the Taisho era through the early Showa era, the influence of Taisho Modernism brought significant changes. While mud-dyeing remained the foundation of Oshima Tsumugi, the introduction of iro-Oshima (colored Oshima) became increasingly popular. Bold and expressive designs, often featuring large-scale depictions of flowers, birds, and natural landscapes, emerged as fashionable trends of the time.

Some designs from that era still exist, and for kimono patterns meant for smaller-statured Japanese people, they are surprisingly large in scale. Moreover, the drawings are extremely detailed—so much so that one can’t help but be impressed they were all created by hand.

Oshima of Showa(1926-1989)

After World War II ended, the entire Amami Oshima region came under American occupation in February 1946 and remained so for nearly seven years. Many producers of Oshima Tsumugi left the island for Kagoshima on the nearby mainland. A mark featuring the Japanese flag can be found at the end of each bolt of fabric; it was originally used for bolts produced in Amami Oshima but is now often seen on Oshima Tsumugi produced in Kagoshima instead.

Meanwhile, members of the cooperative who remained on Amami Oshima worked tirelessly to revive tsumugi while preserving the traditions passed down from their forebears. However, obtaining raw materials was difficult under the occupation, causing production to plummet to 681 bolts in 1950, bringing them to the brink of ceasing production entirely. Yet, driven by the determination of producers who refused to let the art of Oshima Tsumugi die out, they appealed to the U.S. military government and secured “GARIOA” funds. This allowed them to procure raw materials from the Japanese mainland, and by the following year, production had surged to 23,000 bolts. At that time, Amami Oshima adopted the “Chikyu-in” (“Earth Mark”) as its trademark.

Through these efforts, the Amami Oshima Tsumugi Cooperative celebrated its 100th anniversary last year. The fact that Amami Oshima Tsumugi has maintained its high quality to this day is a testament to the dedication of these pioneers. Believing in the promise of tomorrow, Amami Oshima Tsumugi continues to move forward.

名古屋帯

名古屋帯

袋帯

袋帯

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

訪問着・付下げ・色無地ほか

浴衣・半巾帯

浴衣・半巾帯

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

肌着

肌着

小物

小物

履物

履物

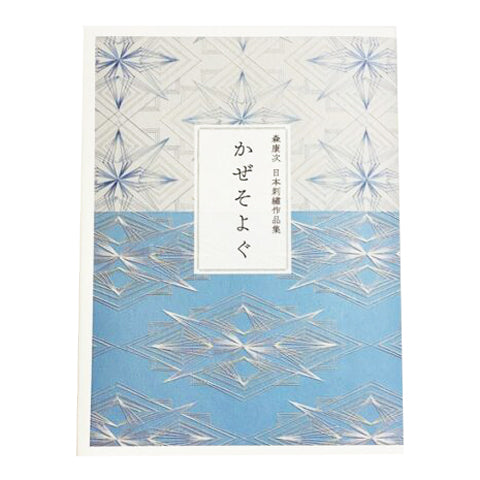

書籍

書籍

長襦袢

長襦袢

小物

小物

帯

帯

お召

お召

小紋・江戸小紋

小紋・江戸小紋

紬・綿・自然布

紬・綿・自然布

袴

袴

長襦袢

長襦袢

浴衣

浴衣

羽織・コート

羽織・コート

額裏

額裏

肌着

肌着

履物

履物

紋付

紋付

書籍

書籍